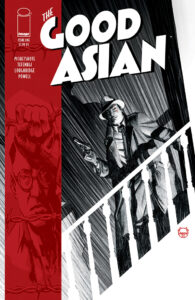

After submitting written questions for the individual interviews with writer Pornsak Pichetshote and artist Alexandre Tefenkgi, I sat down with the duo over zoom to discuss some of the more personal elements of the comic’s development. What follows is a somewhat less packaged, more nuanced discussion of what The Good Asian means to this team. Do keep in mind that there may be some overlap with content covered in the individual interviews. As hate crimes and rhetoric against Asians and Asian-Americans in the US continue unabated, inspiring sweeping national anti-hate crime legislation, The Good Asian‘s social relevance may not have been intended, but it certainly has become undeniable. These candid responses received minimal editing in the hope of recording the creators’ thoughts and expressions authentically for our readers.

ComicAttack: I wanted to touch on the motivation for coming together and working on this story, for bringing it to a mainstream audience. What got you guys together and made you decide that this was a timely story that needed the exposure?

PP: It’s funny, for me anyway. You work on this stuff like so far in advance so like the timeliness of it coming out now as sort this conversation about anti-Asian crime in American and Asian-American-ess and how to be Asian-American in America that I see happening on my timeline right now, it’s always hard to tell how much of that is just me and how much of that is more than me. But of course, this happened so far in advance, you don’t really know the timeliness.

So for me, it was more my backstory, and I feel bad because I feel like Alex has heard this like a thousand times at this point. I self-identify as Thai American, but I’m ethnically Chinese. My father is Chinese, but he was raised in Thailand. So whenever my mom and dad would get into fights about politics, whenever my dad was losing he would just finally say, “Oh, this is the problem with Thai people.” and then my mom would get very annoyed and be like, “What are you talking about, you’re Thai!” And he’d be like, “I’m Chinese!” And my mom would be like, “You don’t speak Chinese, you never lived in China, You’re Thai.”

And so I always identified as Thai-American as a result of that. Leading up to the years before my dad passed away, he was increasingly obsessed with China. And so when he passed away I think part of me dealing with that was getting to know more of my Chinese roots. And probably because I am so interested in Americana, as opposed to being interested in China and Chinese mythology, I got really interested in Chinese-American history. And that’s when I found out about the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Immigration Act of 1924, and I was really embarrassed as an Asian-American not knowing about it.

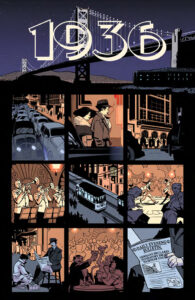

And so that’s when the idea of “I think that’s something that should be talked about” sort of merged with this fascination I’ve had for a while with the Asian detective of the 1930s. Charlie and Mr. Moto and all that. And so the idea that in that last decade leading up to the end of the Chinese Exclusion Act and still new off the Immigration Act of 1924 that limited Arabs and Asians into the country that people could be fascinated with the Asian detective, but still not allowing Asians in a certain category into the country. Let’s do a story about an Asian detective in the 1930s that sort of acknowledges all of this history.

So that’s where the idea came from. And the aspect of timeliness that I thought of at the time was that there is so much Asian American history that isn’t talked about. That’s ignored in this country. So much of it is interesting. Working on this book led me to discoveries. I didn’t know about the anti-Philipino Riots in the 1930s, I didn’t know about the anti-Chinese Riots in the 1970s. When I was growing up, we didn’t talk about Japanese Internment. We’re talking about that a little bit more now. But there are so many facets of that that I feel like we’ve overlooked, it’s really part of Asian American history and identity, but also American History and American culture. So I think that’s where that came in, and it’s been- Interesting is a word for it. To have the announcement for the book happen as the news media both talks about anti-Asian crimes, and doesn’t talk about anti-Asian crimes.

Then in terms of meeting up with Alex, once we knew we had this book, we kind of knew a vague idea of the sort of style we wanted for it. Me, and my editor Will is friends with Cliff Chiang, and Cliff introduced us to Alex’s work. Cliff’s such a great artist that when Cliff says, “Hey, you’ve got to look at this artist,” we’re like, ”Let’s just give him the job. Do we even need to look at his art? Cliff likes him, he’s got to be good.” But then we saw his art and we flipped out for it. The thing I love about working with Alex is, regardless of what you’ve seen he is getting better and better with each issue. It’s so exciting to get new pages from him. It’s so exciting to see him push and grow. It’s been a fantastic experience.

CA: Alex, do you have anything that you’d like to add to that in terms of your engagement with the story and how you came to build on that initial interest?

AT: For me, it was a bit of a funny story how I got on this project because I discovered late that I had Vietnamese roots. So I was in the process of discovering that part of my culture and at that time I was living in Vietnam and I went to New York for the convention. That’s where I met Cliff Chiang, and I talked with him about my background and what I discovered actually about my Asian roots. We talked about life, about [the] Asian community, about work. And he said, “Yeah, you got better with your work so I might have something that could be a fit for you.”

And then he introduced me to Pornsak and Will, and when I read the project I thought, “Wow, that can mirror what I am going through right now in the sense of being one step inside the community and the other outside.” Because I’m not only Asian, I’m also part African. I’ve been raised in France. My father, who raised me, is from Lebanon so it’s all a mix and it’s sometimes complex to define your identity and to define what’s like to be a good part- A good member of a community. So when I read this story I thought, “Wow, that’s great!” I thought it was a great opportunity to have a project like that because I never made a book in this genre. It’s a great opportunity. And so I thought… It was fate.

PP: Yeah, I think so. One of the interesting things I think about what Alex is saying too is that I really relate to what he’s saying in the sense that- In many senses, but in one sense like, my high school years, and sort of those “formative” high school years, I grew up in Thailand. And so I grew up in this country until I was twelve, and then I came back for college. And in a lot of ways because of that, I’ve always felt like an “outsider-looking-in.” In America. Into the Asian-American community as well.

And just hearing Alex say that part of me wonders whether we’re the outliers, or if that’s a part of the Asian-American experience; of feeling, straddling these different cultures and kind of always feeling out even though you know you’re supposed to feel in? And these are one of those things that like, I can’t definitively say. We are a very unscientific group of two when we talk about this, but part of the reasons why I certainly wanted to write the book was to get that conversation and make it public.

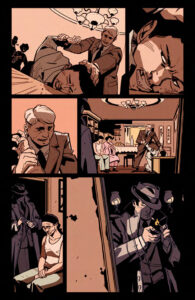

In a lot of ways, that’s what Hark kind of feels like as well. The main character of the book, he grew up in a privileged white family. He was adopted by them and so he feels like an outlier to his own community. And so part of him doing all the things that he does is trying to figure out, “What responsibility do I have to the community, and what is my community? Is my community America, because America says the laws are this? Is my community my fellow Chinese people, because what I’m doing sort of isn’t helping them?”

So a lot of what Alex was talking about, I relate with. And hopefully, it was injected into Hark with this idea of this feeling outside but feeling a certain amount of loyalty, and feeling that conflict that I as an Asian-American feel and I think other Asian-Americans feel. The Idea was to externalize it and make it literal.

CA: Alex, you said that you hadn’t had an opportunity to work on a noir book previously. What is it about that genre, what is it about that style, that made you more interested in working on the project?

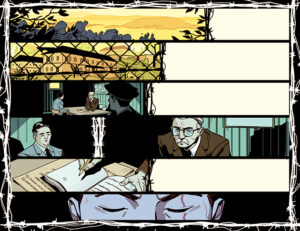

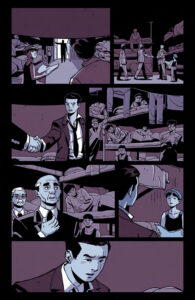

AT: I talked about that in the sense of the mystery, the style… My previous book was Outpost Zero and the style was different. It was kind of similar, but I tweaked my art style for this book and I wanted to add the heavy black in the style without losing what is one of my strengths, expression, and acting. So sometimes I lose the ambiance using the black in favor of the expressions and the acting of the characters. So I always try to find a balance between the ambiance and the atmosphere and what I want to express and my strength as a storyteller with the facial expression and the acting of the characters.

CA: Was there a lot of reference for the Chinatown area of San Fransisco to work with?

PP: There was reference. It depends on what your definition of “a lot “ is. There are some… I can’t remember what they’re called. When I say picture books you think of books for children, but they’re like a bunch of photographs that show Chinatown through the ages, so there’s a couple there from the 30s and 40s. Some of that architecture, big sweeps of that architecture hasn’t changed that much. But it was a lot of research and searching.

In a way, when I script a scene for Alex, it’s almost like writing a screenplay in the sense of, “Okay, we have a new location. Well, I’ve got to get a certain amount of reference for it, so let’s make sure we really use it.” So I don’t have to like, find reference for something else, let’s find something visually interesting so Alex and dig in and not flit around too much. And then, if we have a chance, to come back so I don’t have to find reference again but still find a way for it to thematically resonate with the story. But I know Alex went searching for his own reference on top of that, I’m pretty sure.

AT: Yeah, I want to say that I’m really lucky because all the groundwork, the big heavy lifting is made by you Pornsak. I received a folder with almost everything and then I add and expand the research on my own with Google and Pintrest. But most of the work is already done and I feel really lucky because I can be faster because of that.

CA: One of the characters, Terrence Chang, discussed demonstrating how substantial the economic impact of re-opening immigration would be beneficial to the greater San Fransisco community, outside of just Chinatown, to build popular support for changing the legislation. Was that an actual political strategy that was used at the time and was it effective?

PP: I can’t say if it was. The way you phrase it, and even the way Terrence phrases it, it’s a very specific strategy that was done. I don’t know, or at least I can’t find documentation if it was as clear-cut as that. But what Terrence was referring to is that starting 1936, going up through the early 40s in San Franciscan Chinatown, a circuit of clubs that became known as the Chop Suey Circuit started. And it’s kind of like the Jade Castle in the book, where it’s a bunch of night clubs in Chinatown where Chinese performers would sing and dance and do stand up comedy and live shows, but unlike other theater and other performances done before that, it was all American pieces.

It was Chinese people doing American pieces, and kind of like the Cotton Club in the Harlem Renaissance, it drew a lot of white spectators and people and it brought a lot of business into Chinatown. And it did sort of give the feeling, as more people got there, Chinatown became less exotic. And that was always one of the strategies, is that the more people came there for “good reasons” the less dangerous it was.

Even something like Chop Suey, which is not Chinese food- It was created in Chinatown and it was created as a way to make the Chinese in Chinatown and Chinese cuisine feel less dangerous. And it was something that was made to get Americans to sample the food there and go there. So there was always this sort of sense that the more white people felt safe coming and bringing their business to Chinatown the better it was for Chinatown to be accepted.

CA: And so you have that, while it is becoming more attractive to outsiders, it becomes more of a novelty and less authentic.

PP: Yeah, I mean it is sort of a tricky thing. There were times in Chinatown where the Chinese would pretend to execute- There would be Tong performances where there would be tourism guides that went through and then they would have people pretend to be gangsters being shot on the street and that kind of stuff, just for the sake of these white tourists because they knew that was the show they wanted to see. So you always kind of have a little of that give and take, and that back and forth.

But it’s funny, when you say that it makes me think of a quote by Jay Caspian Kang which I’m going to get wrong, but he said something like, “Whenever you make a stand for authenticity, you end up questioning what constitutes authenticity.” And I think about that a lot when I’m writing the book. Am I the right person to write this book? Am I Asian enough to write this book? Do I know enough about that aspect of my culture, about that aspect of my history to write this book?

And I feel like it’s one of those questions that you always have when you want to show something that you feel hasn’t been portrayed you want to do it justice. I think there’s always those questions of, “Are you the right person to do that?” So I feel like those questions always happen in the course of trying to expand something not seen.

CA: Alex, working on this project did you discover any historical aspects of how Asian people had been treated in the US, particularly Chinese people, where you felt surprised or uneasy about?

AT: Before reading the project, I didn’t know about the Exclusion Act, but for me, I wasn’t surprised or shocked about it because it’s cyclical. It’s always the same, it’s just the time period and a bit of the context are changed. You can translate what’s happening in the book today with the immigrants. Here it was the- It’s the Chinese, but under Trump, there was the South American. And that’s why I wasn’t surprised. Except if we learn for our mistakes, and that’s why also, the book is important. Because we need to learn from the past and to raise awareness about what already happened to avoid doing the same mistakes. That’s why I thought, “Yeah, I didn’t know about it, but I’m not surprised.”

CA: Do you feel that this book can help start raising awareness about the discriminatory policies and experiences that have affected Asian-Americans in the past? Can it help start conversations about more representative depictions of Asian characters, particularly lead characters and Asian stories in the US comics industry?

PP: I think there’s always the hope that stuff like that can happen. It’s a lot to say it’s a goal. I mean, the goal was just having anyone read it. So the idea to what degree any of the stories we tell can change minds, I think there’s always sort of the hope of that being the case and I would certainly be thrilled if that was the case. But right now my concern is more getting people to read it, getting people to enjoy it, getting people to be entertained by it. You know, the book talks about heavy stuff, but one of the reasons it’s packaged in a noir is, I think, noir is a great genre to talk about dark things in the world and the people that fight in contrast to that look more heroic and that much more impressive.

One of the things we’re really trying to do is tell a story with style that’s entertaining, that’s fun even though it’s packaged all that. I would hate for people to think it’s a book about eating your vegetables. We tried really hard to make this a detective mystery with all the things you expect from one of those stories. That to me is the primary goal, is to make something entertaining in this detective genre that I happen to love, and then from there hopefully if anything happened from that I would feel great about that.

And Alex, do you largely agree with Pornsak that representation and historical context aren’t the intent, but can be added benefits of having people enjoy and experience the story?

AT: Yes, I second what Pornsak said. The first goal is to entertain people and make them spend quality time with a good book and at the same time if you can speak about something that is serious; relevant even today, that’s great. So yeah, it’s not a history book, it’s a comic book.

PP: And I don’t want to make it sound like I don’t care about representation and changing minds and all that. But I do think and listen I can get bogged in with this when I’m writing as well, those grandiose themes, those grandiose ambitions- I feel like they are important, and they’re definitely in my mind as far as wanting to start conversations in that direction. But I do think that when you’re telling a story, your first priority has to be the story itself, and the story itself is infused with all those ideas. But after you tell the story I sort of feel like then you say, “Okay. Alright. How does it hold up to these ambitions?” But I don’t think it can be the primary goal, otherwise, the story tends to fall in on itself.

And it would compromise the characters if that was something that was driving the narrative forward.

PP: Also too I feel like, when you lead with your world and your characters, you open up room for your characters to teach you about the world. And sometimes I feel like when you lead with ideology, in a way you shrink the world of the story. You’re doing everything to fit a thesis, as opposed to letting the story explain something about the world maybe you were not aware of.

As always, we at ComicAttack.net would like to thank Pornsak Pichetshote and Alexandre Tefenkgi for taking the time to share their thoughts, experiences, and opinions with us and our readers. Check out my review of the first 3 issues here, and solo interviews for the writer and artist here. The Good Asian is available online and at local retailers now.

Christian Davenport

cable201@comicattack.net