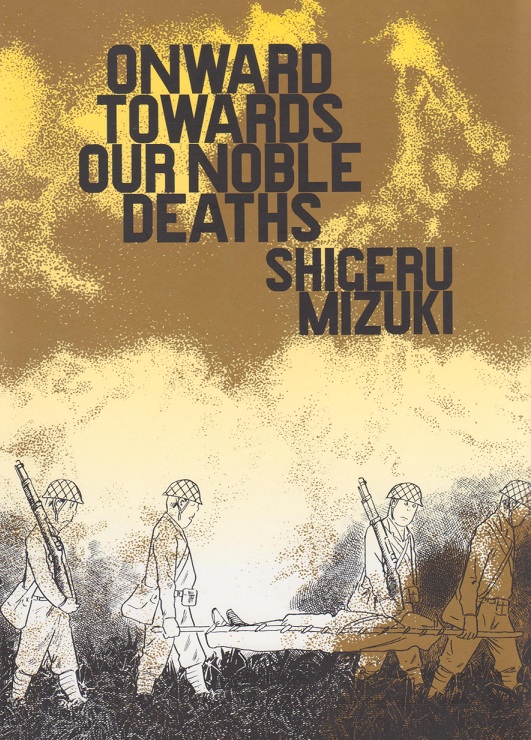

Title: Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths

Title: Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths

Author: Shigeru Mizuki

Publisher: Drawn & Quarterly

Volume: Single volume, $24.95

Vintage: Originally published in 1973 as Soin gyokusai seyo!, Drawn & Quarterly edition in April 2011

Genre: Historical fiction, war, history, WWII, drama, memoir

Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths is a mostly factual, semi-fictional story of a group of Japanese soldiers towards the end of WWII and their “glorious death” on the island of New Britain (Papua New Guinea, near Australia). Shigeru Mizuki’s story can only be told because he was severely injured and sick prior to the assault that led to the deaths of these men, a unit which he would have been attached to otherwise. This particular group of men was stationed in Baien at the end of 1943. Led by the young and zealous Battalion Commander Major Tadokoro, the group of men set up camp on the island of New Britain. Told they would be living in a virtual paradise, morale quickly began to drop after constant rain plagued the men, and supplies began to run out as Allied troops began to invade the island. As the troops closed in, and more continued to land, the Japanese soldiers were cut off from their supplies and sources of food and water. Many of the men grew sick with malaria, most were starving and weak without food or adequate water supplies, and many lives were lost to freak accidents, bombing raids, and enemy attacks. With visions of his military heroes swimming in his mind, Major Tadokoro, against the advice of his officers (who recommended a retreat into the mountains for guerrilla operations, which would have allowed the men to last for another month or two), ordered a final suicide attack against the enclosing enemy. His orders were sent back to base, and it was announced that his unit had died in honorable battle. Unfortunately (in this case), many of the men did not die, and came back, essentially disobeying their orders and abandoning their duty. Because their suicide charge had already been reported, the men were promptly sent back into battle to die, to avoid embarrassing the army.

The commanding officer, Major Tadokoro makes me furious, which I think is exactly the point. Mizuki himself says in the afterword that thinking about war makes him blind with rage, and he conveys this feeling by making the reader feel the same way through his presentation of the war. I really wanted to punch Major Tadokoro in the face and say, “Why do you want to waste so many lives?” Similar phrases come out of the mouths of the characters in the story. The feelings of the characters in the story reflected so well my own feelings while reading. Mizuki conveys real, human emotion from page to page, giving a very human perspective to the Japanese side of the war, a side that contradicts what we as Americans are taught in our history classes. We’re often taught that the Japanese soldiers were vicious monsters, who would sooner fight until every one of them was dead rather than end the war, which was in large part the reasoning behind our dropping of the atomic bombs on their country. Yet, in Onward Towards…, we have a young, idealistic commander filled with youthful notions of honor, of victory in death, shame in defeat and retreat. And these ideals were shared among many of rank, but among the simple soldiers portrayed by Mizuki, there is a feeling of futility and confusion. These are normal men with families and lives back on the main land, and they just want to make it back home. Some of them are far more concerned about where their next meal will come from than of how to maintain control over a strip of land. It’s very humanizing. Major Tadokoro is given other options, and shown brushing them completely aside in favor of a noble charge into death. It’s repeated several times that retreating into the mountains and switching to guerrilla tactics would allow the men to hold out for another month or two. In a time when the war was nearing its end, and just across a strip of water over 100,000 soldiers were idly biding their time, it seems ridiculous to sacrifice the lives of so many men for a tiny piece of land. However, the Major insists it is their only option, and forces his men to accept his desires with his order (because disobeying an order is about the worst crime you could commit; you might as well join the suicide charge, because you’ll just have to commit ritual suicide if you disobey). The futility of this is astounding, and it’s quite clear that Mizuki feels the decision wasted a great many lives and destroyed many families.

One of the most important things illustrated in Mizuki’s story, is the treatment of the rank and file by the officers. In the foreword, Frederik L. Schodt notes that Mizuki himself was regularly beaten by those ranked above him, because he was a low ranking, “rookie” soldier. When Mizuki miraculously escaped the demise of his own unit, he was reprimanded for leaving his weapon behind and, in classic style, for surviving. He uses these experiences throughout the book, as the soldiers are frequently smacked around by their superiors, often for no reason at all, or simply to prove that they were less than human, no better than dogs. It really made me cringe every single time.

Drawn & Quarterly’s treatment is superb. The art remains in its traditional format, which will probably lose them some sales, but is hugely appreciated by those of us who prefer to read manga in its original format. The cover treatment is wonderfully understated, and the volume contains an excellent foreword by Frederik L. Schodt (whose Dreamland Japan I will be reviewing in the next month or so), an afterword by Mizuki himself, and a recent interview with Mizuki at the back. There is also a good section of notes in the back, alluded to through the volume, which I shall only complain about as I personally hate having to flip to the back of a book for footnotes. It makes the rest of the book very neat and clean, but there’s also plenty of margin space around the panels. Every panel is high quality, the text and translation are easy to read, and there’s a nice listing of all the main characters at the front of the book with a picture of each character’s face along with their name. It’s a lot of faces and names to learn, and the fact that I didn’t bother to study them led to a tiny bit of confusion later on, but with the way the story flows, it’s really only important to keep track of a few specific people. Which actually makes me feel a bit bad, as I suspect part of this book’s purpose is to give a face to the otherwise faceless mass of men who died in the war. As for Mizuki’s art, the men are drawn in a cartoony style over highly detailed backgrounds, which makes things a little off putting when body parts start flying everywhere. The juxtaposition is nice, and it makes the carnage more disturbing than it might otherwise be with more realistic artwork. It’s definitely a dark book, and it’s also moving and infuriating (which it’s supposed to be). I highly recommend picking this up, and it’s very much worth every penny.

Kris

kristin@comicattack.net

@girlg33k_Kris

Kristin- I actually purchased this book. Haven’t read it yet, though.

Pingback: Censorship, disasters, and the glorious Manga Revolution « MangaBlog

I’ve heard a couple of good things about this from my friends who really like stories from this era. Just may check it out myself pretty soon.

Andy, get on it already!

IS: At the very least, borrow it from your friend. It’s very good.

Pingback: Bento Bako Weekly: Dreamland Japan