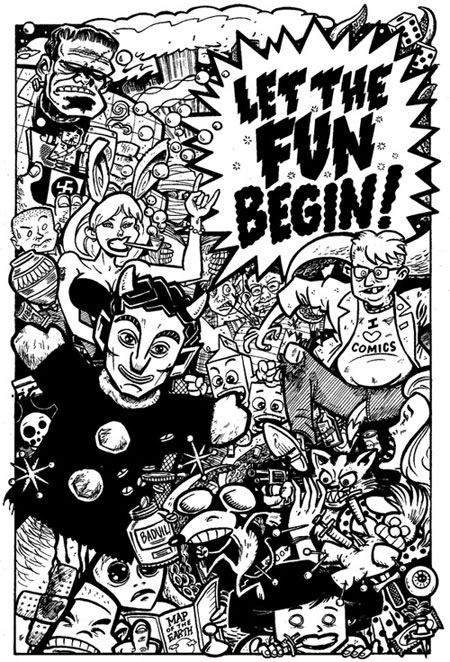

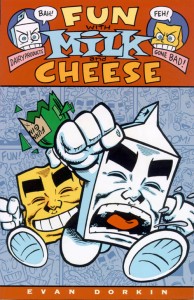

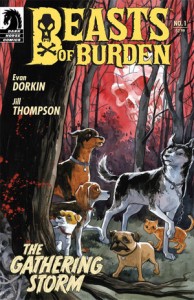

May’s Artist of the Month is none other than Eisner Award winning artist Evan Dorkin! Throughout his professional career in comics, which spans close to three decades, Evan has often lampooned fandom and pop-culture, only to be embraced by both. Although ComicAttack.net is honoring Evan for his talents as an illustrator, don’t let that overshadow his skills as a writer. He co-wrote the first three seasons of Space Ghost Coast to Coast, as well as four episodes of Superman: the Animated Series. In addition, he wrote and illustrated Fun with Milk and Cheese, Bill and Teds Excellent Comic Book, and Dork! (which features the Eisner Award winning Eltingville Comic-Book, Science-Fiction, Fantasy, Horror, and Role-Playing Club), to name a few. Evan Dorkin’s uniquely detailed illustrations and eclectic writing style have earned him a well-deserved cult following within the comic community. Although I would describe Evan as an indie darling, he would adamantly disagree. Evan’s perfectionist nature often clouds his ability to recognize his own creative genius. This blurred self-perception has contributed just as much to his successes, as it has his failures. Regardless, Evan has produced some of the most innovative comic books of my generation, and the integrity of his work is only surpassed by his candid nature. Evan’s tendency to scrutinize his own projects may cause him to internalize many of his self-directed criticisms, but he’s anything but short-winded. In this exclusive interview, he talks about his early artwork, the challenges of writing Beasts of Burden, and the future of Fun with Milk and Cheese. Plus much, much more. So without further ado, let the fun begin!

May’s Artist of the Month is none other than Eisner Award winning artist Evan Dorkin! Throughout his professional career in comics, which spans close to three decades, Evan has often lampooned fandom and pop-culture, only to be embraced by both. Although ComicAttack.net is honoring Evan for his talents as an illustrator, don’t let that overshadow his skills as a writer. He co-wrote the first three seasons of Space Ghost Coast to Coast, as well as four episodes of Superman: the Animated Series. In addition, he wrote and illustrated Fun with Milk and Cheese, Bill and Teds Excellent Comic Book, and Dork! (which features the Eisner Award winning Eltingville Comic-Book, Science-Fiction, Fantasy, Horror, and Role-Playing Club), to name a few. Evan Dorkin’s uniquely detailed illustrations and eclectic writing style have earned him a well-deserved cult following within the comic community. Although I would describe Evan as an indie darling, he would adamantly disagree. Evan’s perfectionist nature often clouds his ability to recognize his own creative genius. This blurred self-perception has contributed just as much to his successes, as it has his failures. Regardless, Evan has produced some of the most innovative comic books of my generation, and the integrity of his work is only surpassed by his candid nature. Evan’s tendency to scrutinize his own projects may cause him to internalize many of his self-directed criticisms, but he’s anything but short-winded. In this exclusive interview, he talks about his early artwork, the challenges of writing Beasts of Burden, and the future of Fun with Milk and Cheese. Plus much, much more. So without further ado, let the fun begin!

Comic Attack: When did you first start creating your own comic strips? How would you describe the stories and artwork in those first ventures?

Evan Dorkin: Like a lot of folks, I made my first comics when I was a kid. The things I remember drawing early on were little monsters and space aliens, and copying characters from the Peanuts strip out of the newspaper. When I was older, I made comics with Marvel superheroes, which were all terrible, [and] I didn’t know how to draw anyone who wasn’t wearing a mask. So, I’d always have a character like Reed Richards stand about fifty yards in the background, and I’d never draw Johnny Storm with his flame off. I recognized my weaknesses, but instead of working on them, I came up with loopy contrivances to get past them. The Invisible Woman was always invisible, because I couldn’t draw girls… or wouldn’t. I really wish I’d kept those awful kid’s comics. Because I’m sure they’d be hilarious, like kid’s comics usually are. But I threw everything out, I have none of my childhood art, and only [have] a few things I drew before my twenties. Actually, I don’t have much art from my twenties around, either. I was constantly throwing my art and comics in the garbage. So, I guess I’d describe the art and stories in my early comics as garbage.

CA: How long were you employed at Jim Hanley’s Universe in Staten Island, NY? Did working in a comic shop affect your artwork and writing as a comic creator?

ED: I worked in retail for about six years, I’d guess, off an on, between two shops: The Fantastic Store and Jim Hanley’s Universe. I was fired a bunch of times for being a dick, but it only stuck once. Maybe twice. Working at the shops definitely affected my outlook on comics. Jim was into all different kinds of comics. He stocked them, and [he] talked them up to the employees as well as the customers. I started reading old newspaper strips, The Spirit, Love and Rockets, [and] other things on his recommendation. When I first worked at The Fantastic Store, I was earning two dollars in trade and two in cash. I saved up to buy the Russ Cochran Tales From The Crypt EC library slipcased set. It took me a while to save enough, and I remember lugging that sucker over a mile back home because I didn’t drive at the time. Between Jim, the staff, some of the customers, and having all these comics at my disposal, it was a real education. It was like being a musician and having a job in a guitar shop. I got to learn about the medium, about the field, and meet some professionals and amateurs – including a writer named Alan Rowlands who dragged me to a few meetings with editors from Marvel, DC, and the small press outfits that were popping up like whack-a-moles in the wake of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles craze. That led to my first gig, as well as meeting the people who would later start Eternity Comics and publish my first solo book, Pirate Corp$! I also met Fabian Nicieza during a dinner at the San Diego Con in 1988. Jim Hanley set up a dinner with some Marvel sales people. Fabian later became an editor at Marvel, and [he] hired me to do the Bill and Ted Comic. Before I worked at the Fantastic Store, I was pretty much sealed off from organized fandom. [I was] largely ignorant about the medium, the industry, and how comics were made. Until my late teens, I was doing all my comic art at the same size that comic books were printed at. I didn’t know what a rapidograph was, that you used a brush to ink with (I was using a cheap department store cro quill pen at the time, I never really did get a handle on using a brush), [and] that there was white correction ink for mistakes. I had no mentor, no older brother, or [no] relatives who knew about art or liked comics. In many ways, working at the shops with people like Jim was my mentoring process. At least, [it was] an eye-opening experience regarding the medium, its potential, and how various cartoonists approached comics. Too bad I was always acting like such a dick. If I worked in a shop now, I wouldn’t act the same way. At least, I hope I wouldn’t. I hate clerks who act the way [that] I did: rude, opinionated, [and] snarky. I could hand-sell comics with the best of them, and I knew my stuff. But I drove everybody up the wall, and [I] pulled some stupid shit. You live and learn… and get fired.

CA: As a writer and artist, how does your personal illustration style complement your particular brand of story-telling?

ED: It clutters everything up, and causes problems. It often gets in the way of what I’m trying to do. I overwrite. Then I draw too much in a panel and on a page. I try to cram too much into a project, and it often dampens the impact of a piece or cramps the flow of a sequence. It’s a compulsion and a problem. Even when I vow to keep a drawing or a strip simple, I start noodling on it, and often screw it up. [It’s a combination of] lack of training, lack of confidence, inability to make a clear decision quickly, [and] a need to be seen as trying to do my best. Even if I tell myself [that] I must draw decently enough to have gotten the job at hand, I become anxious [that] I’m going to do a bad job, and often overcompensate with detail. Sometimes it works; sometimes it’s distracting and unnecessary. As if I’m trying to make up for my lack of chops with more bad drawing or something. It makes no sense. It’s like putting gravy on bad meat and hoping it will cover up your mistakes. I have a lot of ambivalence about my artwork, even moreso than with my writing. Before anyone was looking at my work, I didn’t really have a confidence problem. I knew my stuff was rough, but I also assumed I’d improve. When people started paying some attention to my work, I started doubting everything I did, and it just inflated my working process. I’m still trying to shake off these compulsions and doubts, but it’s hard. I feel this need to make everything the best it can be, knowing full well that’s not possible. I’m not a master artist or brilliant writer. At least I’m not frozen stiff, as I was years ago, when I couldn’t make any decisions at all and had panic attacks over my work. I ruined a pilot project at the Cartoon Network because of that, which still haunts me. If you just look at the way in which I answer these questions, you’ll see I have a tendency to overdo things. I always feel like I haven’t explained myself clearly, haven’t done enough work, or have more ideas that I can cram in to improve something. It’s probably going to be a few more decades before I get over this… if I ever do. I guess I’m a maximalist. And a neurotic.

CA: What motivated you to pursue a degree in Film and Television from NYU? After receiving your degree, was there any change in that motivation?

ED: I went to film school because I wanted to study animation, and become an animator. It was my goal from about the age of thirteen or so. I was obsessed with cartoons and animation, including model animation, which I had no talent for. I made a few awful home movies with my Super-8 camera [by] moving crap around and clicking off a frame or two, but I was a big animation geek. I went to animated films by myself , studied the cartoon shorts on television, and bought Funnyworld magazine. [I] read anything on animation I could get my hands on, which unfortunately, wasn’t much. So, I went to NYU. My folks wouldn’t pay for SVA, which is where I wanted to go to learn traditional hand-drawn 2-D animation, key poses, fill-ins, [and] cels. Obviously that didn’t work out as planned. Animating something wasn’t wholly beyond me, [and] I did fairly well in that area. However, everything else involving filmmaking was a struggle. I’m an imbecile when it comes to anything technical or mechanical. Even basic things. So, when learning about live action film, I couldn’t light a shoot, I screwed up light meter readings, and I fumbled a lot while working with the editing and [the] camera equipment. This was a bit of a problem for me. I couldn’t even work a 35 mm camera correctly all the time, in my photography course, and it was my own family’s camera [that] I was using. [While] working on my final sound animation reel, I made a last-minute mistake, and punched holes in my soundtrack. I set the magnetic track up incorrectly, and the sprockets punched the thing full of dents. I only got through my classes because my ideas were sound, or at least they were judged to be sound. So, I veered towards screen-writing classes along with my animation courses, and found I preferred writing to anything else I was doing. I was also turned off to film by being around film students all [of] the time. On the whole, they were a miserable, self-absorbed, shallow, [and] pretentious bunch. I would sit in the back of class and draw comics like a high school kid, while they prattled on about their big ideas to become the next Spielberg. Of course, they were all technical marvels. They had nothing to say and said it terribly, but their films were fairly slick. There were some great people, some talented people, and some great instructors. But overall, it was pretty depressing and a real turn-off.

CA: Although you’re primarily known as an independent comic artist within the fan community, your work has been published by Marvel, and you wrote some episodes of Superman the Animated Series. During your time on these projects, have you ever turned down an opportunity that could have led to a more mainstream career as a comic artist?

ED: I turned down a few mainstream jobs that might have done well for me back in the 90’s. [I was offered] a gig to co-develop and co-write X-Men 2099, and write a Black Panther 2099 series. I [also] turned down an offer to write The Flash a ways back. I don’t think I could come up with enough ideas for a character who’s supposed to be fast enough to solve his problems by page three. If superhero comics were as realistic as folks say they are. The Flash sees a problem; the Flash takes care of it. Boom. Done. I’m either not clever enough, or not invested enough to figure out how to contrive all the stuff you need to tell a Flash story. [Like] all the things that negate or screw up his ability to run over and fix something by page three. Too crazy for me. Anyway, I didn’t take the 2099 books for reasons that had to do with my small-press work, and Marvel’s attitude toward small-press publishers in the day. They had a marketing guy who told retailers not to buy anything from the small-press, to not waste their money, [and] to buy more Marvel books. That’s his job I guess, but I couldn’t see working for Marvel while they were working against the small-press [industry]. Which I was a part of, and still am. It wasn’t just that, though. After I stopped working for Marvel in 1993 or so, I was busy with other projects, especially my own work. So, my schedule had something to do with turning down some jobs. In the case of the Black Panther 2099 job, I didn’t feel I could pull off writing the African characters convincingly and accurately. At least not back then. Even now, I’d only attempt something like that after doing some massive amounts of research. I had an overview for a 12-issue arc, which I liked very much, [with] a new origin for a female descendant of T’Challa, a supporting cast, [and] villains. What the hell did this jewboy from Brooklyn know about Africa? I could have probably worked hard and pulled off a single issue, maybe, but an entire series? I didn’t want to screw up big-time and embarrass myself . Also, I didn’t want to insult the readers, black or white. As a matter of fact, I recently found a sketch of one of the Panther villains in my files. [It was a] stand-in character for the Red Skull. It reminded me of what a weird time it was for me in comics back then. Because, as far as the kinds of comics I would work on, I didn’t know where I was heading: superheroes, small press, [or] humor books. I was juggling a lot at the time, and I guess I still am. The thing is, superheroes in and of themselves aren’t a problem for me. The baggage [that] they come with is. I’ve worked on superhero and mainstream stuff. I don’t dislike superheroes, just what’s done with them most of the time. If a project comes along that looks like fun, and something I can do, then I’ll do it. I tend to like working on projects that don’t involve company-wide continuity or office nonsense. Which means I usually end up working on things that no one cares about. Which is okay with me. I’m rarely offered anything big anyway, at least not from Marvel or DC. So, the issue [of big projects] doesn’t come up [very] much. And it seems when I do work on anything that might be a game-changer, career-wise – a tv pilot, or a book with a decent profile – it either fizzles out, or turns into a bit of a disaster. Of course, that happens to a lot of folks. You mostly hear about the successes in any field, and for every one of those [successes], there’s a bunch of projects crashing and burning on the airstrip. Mine tend to blow up a few feet off the ground.

CA: You and your wife, Sarah Dyer, have collaborated on quite a few projects together. How would you describe your creative relationship with her?

ED: I think it would be more revealing to hear her side of things. As she has to put up with me, and I’m the nervous wreck of the family. I’m better than I used to be. I used to freak out, and think everything we were doing was terrible. [In contrast], Sarah’s easygoing and gets things done. She makes decisions and doesn’t go off on tangents, or get stuck considering endless plot or dialogue possibilities. She’s very good at structure and logic. We usually plot together, and brainstorm ideas for a project before one of us starts a draft. Sometimes she’ll take a script and run with it, or sections of it, or I’ll work alone and we’ll punch it up and polish it together afterwards. We don’t sit down together and write a script straight through. We bounce it back and forth. Then [we] work on the final draft, and any revisions.

CA: What was the level of your creative involvement on Space Ghost Coast to Coast during your five year tenure as co-writer for the series? How much of your original vision for each episode actually translated into each completed episode?

ED: They were extremely generous to us. Along with Welcome to Eltingville and Yo Gabba Gabba, it was the best experience we’ve had in our admittedly limited television careers. When we visited Atlanta to do some work at the Network, we were asked if we wanted to sit in with the editor to go over cuts and details on the Zorak episode that we [had] written. On that same episode, Mike Lazzo wanted to cut the epilogue that takes place in heaven. He wasn’t crazy about it, but we were. So, he let us keep it. I always thought that was incredibly cool of him. They trusted the creative people they hired for the show. You’d think that would happen more often, but it doesn’t.

CA: The dialog and plot from your run on Space Ghost Coast to Coast was non-linear and somewhat abstract, to say the least. How would you describe the process of scripting an episode?

ED: Everyone’s dialogue was non-linear, at least much of the time. I actually think our scripts are more linear and more narratively-driven than most of the others. Maybe that was a liability. For the most part, I just didn’t go for the non-joke/ joke approach. For good or bad, I’m more literal-minded and grounded. Some of the scripts just go for broke, as far as avoiding traditional gag/set-up/punchline/storyline stuff. Which is great, but we generally worked in a more straightforward manner, and structured our scripts more heavily than some others did. That being said, everyone pretty much worked in the same way. Which meant watching interviews with some low-level celebrity. Then chopping up the interview and using bits and pieces to make up a script. It was a cut and paste method. Sort of like William Burroughs, only without the heroin and the gunplay and the boys and all. Sometimes you took the footage and built a script around it. Sometimes we had an idea already sketched out for a show and asked for certain guests – as with Cookout or Lawsuit – and then we took the footage and worked it in. If i recall correctly, the interviews were initially done with a staff member or someone acting as Space Ghost for the guest to react to. Sometimes the guest was in a studio far off , and the questions were fed to them over the phone from the studios in Atlanta. Sometimes they’d interview folks at a comedy festival or some event. Early on the guests didn’t know what the hell was going on and the reactions were gold. Those were the best interviews. Those and the ones with genuinely funny people or geuinely weird people. As time went on, and the show became a sort of cult success, and record companies were trying to get their acts on the show. The guests got wise to what was going on, and were much more defensive and on guard. Which kind of sucked, and made things harder for the writers. Or at least us. But yeah, basically, people were interviewed, and the interviews were chopped up and used to whatever degree was desired by the writers. We’d cut people off before they could plug their projects, we’d insult them and their careers, [and] have Zorak and Space Ghost argue with them or shoot them. It was a lot of fun. I miss it sometimes.

CA: What led to your departure from the show?

ED: We were offered a deal to develop a pilot based on the Eltingville Club comics for the then-unannounced Adult Swim. We simply stopped working on Space Ghost to work on the pilot. Or as I like to call it, the failure.

CA: Speaking of the Welcome to Eltingville animated pilot (adapted from an Eisner award winning story of the same name), why didn’t Cartoon Network pick up more episodes of the show?

ED: I couldn’t tell you, exactly. From what I understand it was an expensive pilot. I think they misjudged how well things would go with the Adult Swim slot, and [they] budgeted the pilot more like a regular prime-time piece of animation. Obviosuly, the response and interest we got wasn’t what they were looking for. I don’t think Mike Lazzo liked the show. Which would [have been] an instant knife in the heart, and I’m assuming that’s what happened. No one’s ever really given me an exact reason. I’m inferring all this. I didn’t hear from them for ages, and even then, producers I spoke with would just talk about it as if everyone knew it was dead. But the words, “no”, or, “we’re not picking it up”, or, “that sucked, sorry” [were] never were spoken to me. They offered me another pilot afterward. So, they didn’t write me off completely. That didn’t happen until I screwed up the second pilot in an extended fit of flop sweat. I don’t blame them, I couldn’t make some minor decisions on the already approved bible, I froze, and eventually they shelved the project. I’ll never live it down, because I screwed myself out of a pilot [that] I wanted to do, I screwed Sarah out of her position on the pilot, and [I] pissed away the work we’d both done on it. Despite my indecision, I really wanted to see it happen. It would have been good. (CA: click here to see the full pilot)

CA: Despite the fact that Welcome to Eltingville wasn’t developed into an on-going TV series, were you pleased with how the pilot turned out?

ED: Kind of. I would do a lot of things differently if I could take another shot at it. I’d punch up the script – actually, I probably wouldn’t go with the story that I chose to adapt, I would have done something that didn’t give some folks the idea that the show would consist of four guys yelling trivia at one another. I’d have the characters re-designed. If the show had been producded a little later than it was, we could have gone more over the top as far as language and violence went. Which I would have taken advantage of, making the show more like the comics. I would definitely have taken on fewer responsibilities. The pilot is a real like/dislike thing with me. It sort of ruined my financial life, through no one’s fault. I put too much time into it, and it didn’t pay off in any way whatsoever. On the other hand, I got to make a pilot, and they pretty much left me alone and backed me up. Not many folks get to do that. As you can probably tell, I’m pretty ambivalent about it. Some folks enjoyed it, and that counts for something, I still get mail and questions about it. Which is pretty cool. Certainly more people watched the pilot than will ever read my dinky comics.

CA: Can fans of your work expect a Fun with Milk and Cheese cartoon anytime soon?

ED: No. I just had an inquiry from a cable network this past week, in fact, which is something that hasn’t happened in a long time. I’m not looking to sell them off, I’m too fond of them. And since the offers are always insulting, I’ve never even been seriously tempted.

CA: Do you have any plans to create a new Milk and Cheese comic series?

ED: The eighth issue has been planned for over a decade now, but I can’t afford to work on it for any serious length of time. Being older and having a family, I can really only manage to get a strip done if someone’s paying me something for it, and that happens very rarely since all the anthologies that I used to contribute to are gone, and no one with a budget of any kind asks me for any new material. I still have hopes to find the time to work on new Milk and Cheese material, and new Eltingville stories, to finish off some things I started in the 90’s. Fingers crossed.

CA: I’ve read numerous amounts of comic books that were based on films. To date, Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey is the most original movie adaptation that I’ve ever seen or read. How did Marvel respond to your version of the story and the variation in the characters’ appearances, especially the Grim Reaper?

ED: Marvel wasn’t paying any attention to the book, it was just another licensed kiddie book and only older professionals who were hankering for work and young amateurs like myself who were hankering for work were getting hired for them. Because no one cared, they let me have a lot of freedom on the book. Marvel never asked me for a significant change in the series. Nelson Entertainment, the company that owned Bill and Ted at the time, did ask me to change one or two things in a script because they were afraid it would offend somebody. The way I drew Death was a bit of a situation, though. I adapted the Bogus Journey movie from the script, and I had assumed Death was going to be a skeletal figure. I didn’t know he was a Bergman parody, the script didn’t describe him as such – at least not in the draft they gave me – and I didn’t have stills of the character until after I started turning in pages. Fabian [Nicieza] told me to just go with the skeletal Death after the point was raised. The schedule couldn’t absorb going back and changing everything, and we liked him as a skeleton anyway. Nelson [Entertainment] didn’t flip out, so he stayed a skeleton. For the comic it worked out well, he was probbaly my favorite character in some ways. Fun to write, [and] fun to draw. The readers seemed to like him a lot.

CA: Did your unique vision of the Bill and Ted universe lead to your on-going gig with Marvel for Bill and Ted’s Excellent Comic?

ED: I think it was less my “unique vision,” and more the fact that nobody really wanted the job. I was hired to do the book while I was still working on the movie adaptation, and the decision was made to do an ongoing series. Initially, I [had] agreed to only do the first four or five issues, but I enjoyed the work and the money. So, I stayed on. I ended up doing the entire run, save for one issue, when I was falling behind schedule [and] working on a three-part story. We were always close on the deadlines on that book. I’d be doing plots or finishing pencils on the Staten Island Ferry heading in to the offices to deliver the work. It was crazy, but fun. Back then, I could pencil a book in several days if I had to. I wish I could do that now.

CA: In 1993, you wrote and illustrated a one-shot for Marvel Comics called Everyone Hates Fight Man. Based on that experience, would you ever consider illustrating and writing an ongoing series within the superhero genre again, Fight Man or otherwise?

ED: I’d be more than happy to write a Fight-Man series. I’m very fond of the character, and I was very happy to bring him back when I wrote two fill-in issues of Agent X in 2003 that had him as a guest star. Every ten years, I get hired by someone at Marvel to waste their money, apparently. I’m gearing up for 2013. Hopefully someone’s getting that Fin Fang Four/Fight-Man contract going as I type. As far as the art goes, I don’t think I’d be asked to draw anything like that, and I don’t know if I’d want to work on something like that. At least not for DC or Marvel. I think it would take me ages to do a straight superhero page. I’d be aching it, and I don’t know if I could pull off that style, or something close to it, to a degree that readers would respond positively to. My artwork’s become more cartoon-ish over the past few years, but who knows. I’d consider almost anything, really. Sometimes you need work.

CA: With your run on Dark Horse’s Beasts of Burden, you successfully accomplished a difficult task by taking a group of domesticated animals, and quickly forming them into likable, well developed characters. What was your approach for establishing each animal’s personality, and were there any specific challenges that came with creating such relatable dialogue for a cast of cats and dogs?

ED: The first comic we did with the characters was written as a stand-alone story. We weren’t planning on developing a series. We were just telling one story about a haunted doghouse, and how these animals were dealing with it. The breeds were chosen to fit the rough characterizations that I [had] laid out for the cast. Before I had names, I had a number of types: a nervous dog, a cynical dog, a tough dog, a steadfast dog, etc. I went through breeds, and cast them to go with the personality types and wrote their dialogue accordingly. There were no long-term plans. It just developed over time, and as we did more stories, the personalities began to take better shape. As far as the dialogue goes, the difficulty pretty much lies with the fact that I’m working with a limited vocabulary. The animals generally don’t know about human culture to a large degree beyond what they observe and hear about. They don’t know anything about pop culture, so I can’t make references to that. As far as I know, There are no pop culture references in the book, and that’s something I’m a little surprised that no one has picked up on. Because I’ve been accused in past projects of doing nothing but referencing pop culture. These characters don’t know anything about movies or comics. So, all those reference points are out. As are a lot of things cultural. Some of their information is hearsay, and they don’t have the same nomenclature for everything as we do. So, there definitely are times where I’m hamstrung by their alien culture and limited knowledge. On the other hand, it’s fun to make up aspects of their animal cultures and belief systems, to play with language and try to see things through their eyes to convey their reactions more interestingly. I try to pepper the dialogue with references to their animal cultures when it seems appropriate, to sprinkle in references to their deities, local events, animal concerns, and their own urban legends. The way people tend to speak throughout their day. Regarding their personalities, I try to give them all speech patterns that are fairly consistant and unique, and I try to make the dialogue seem natural, even though its [being] spoken by talking dogs and cats. Sometimes its difficult, especially when I’m dealing with exposition or a mystery. I wish I could fall back on having a character use a computer, or get characters on a cell phone, or what have you. It can be frustrating to have to explain everything without certain narrative devices that help speed things up in a comic about human beings. I don’t want to use descriptive narration too often. I used it in the first story and then continued to use it off and on afterward, mostly to set up a mood or cover lost time. When I do slip up and a line of dialogue stinks like day-old fish in the sun, my editor, Scott Allie, usually catches it. I had a character say something that was really awful-sounding, out of character, out of species. And he called me on it and said, “Really? He’d say that? Really?” I felt like an idiot. What else is new. I do the best I can. There’s the answer, really. I think about what makes sense in a situation and do the best I can.

CA: What is the primary inspiration for your eclectic series of monster illustrations?

ED: There are several reasons I’ve been doing those little monster drawings. I’m primarily drawing them for my daughter Emily. They’re “her” monsters. It’s also to give myself something fun to draw because I find drawing difficult, and not always enjoyable. The third reason is that I inherited some art supplies when my brother-in-law, Josh, passed away, and I wanted to to do something special with these two little drawing pads of his. “Special” isn’t the right word, maybe “commemorative” is closer. Although, drawing silly monsters doesn’t seem very commemorative, I don’t know how else to put it. But I thought drawing to entertain Emily was a nice way to use Josh’s paper, and I think about him a lot when I work on them.

CA: Throughout your career, you’ve been involved in many successful artistic and literary ventures. As of now, what would you consider your quintessential work, and why?

ED: Ugh. Um…I guess the second strip from Dork #7, Cluttered, Like My Head, because it’s got autobiographical elements in it, and it’s different from anything else I’ve done. It really seemed to hit home for a lot of readers. I received a lot of feedback on that strip. I’m not comfortable thinking in terms of my work as artistic or literary, and calling them successful makes me want to [respond with] a lengthy reply on the relative nature of “success” in comics. I only appear successful in comparison to cartoonists who are even less successful than I am. My resume is much more impressive than my bankbook.

CA: What projects are you currently working on?

ED: We’ve got the Beasts of Burden hardcover collection coming out in June, and Dark Horse just announced a Hellboy/Beasts of Burden one-shot comic that I’ll be scripting, and Jill Thompson will be painting. I believe Mike [Migolia] is doing a cover for the book as well. The crossover was his idea, which kills me to no end. I’m also working on some material for Bongo, writing and sometimes drawing for the Bart Simpson comic, as well as this year’s Treehouse of Horror special. I’m also still doing stuff for Mad Magazine, mostly illustrations. Sometimes I take a short break and work on a gag strip for Dork or a Milk and Cheese panel. I think that’s it at the moment.

CA: Anything to add?

ED: Don’t ask me to add, please. I’m terrible at math. I got a 32 on my Trigonometry regents.

CA: I concur. Math is the Devil.

Now, for an exclusive look at some of Evan’s previously unpublished illustrations with artist’s commentary:

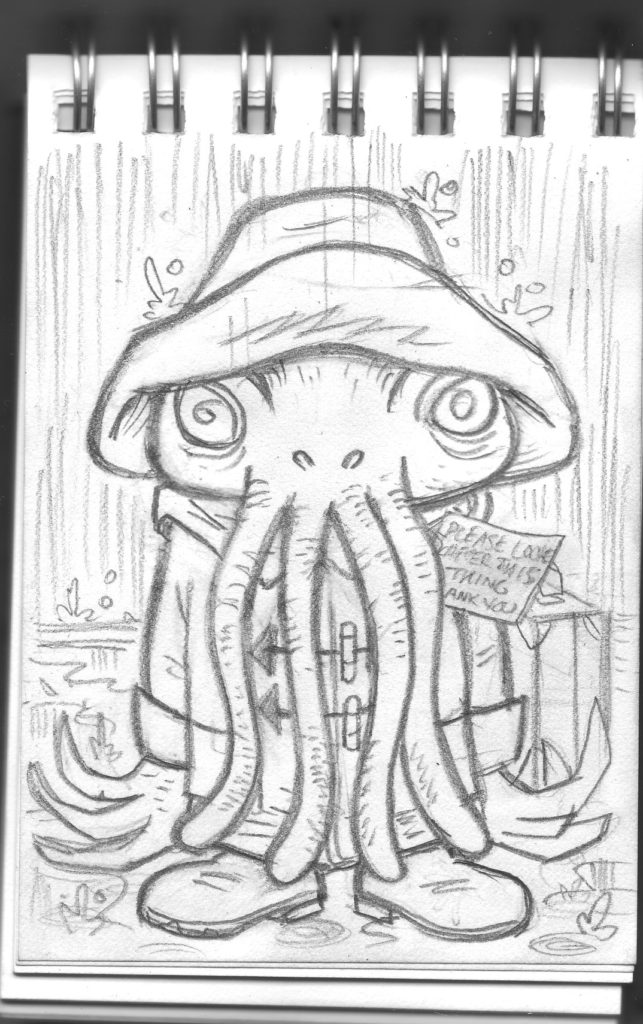

“This is the penciled version of a monster drawing for Emily that I screwed up in the coloring stage and have to redo. It’s a Cthulhu-meets-Paddington Bear monster. I don’t know where the idea came from, to be honest. I probably ruin one out of every four or five of these drawings in the coloring stage because I don’t know what I’m doing when it comes to color, it’s all trial and error.” -Evan Dorkin

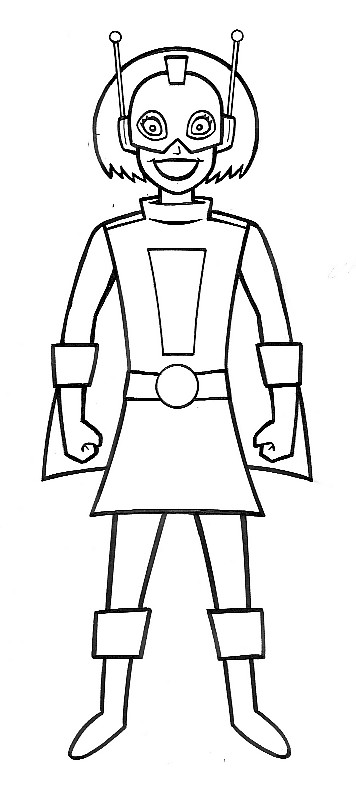

“Super Martian Robot Girl redesign for season three of Yo Gabba Gabba! We designed the character’s outfit and art-directed the flash shorts from season one. For some reason the Nickelodeon executives couldn’t stand the segments even though viewers seem to like them. She didn’t appear in season two but we got to bring her back for a Story Time segment for the “Superhero” episode, which we co-wrote with Christian Jacobs. These are a lot of fun to work on and represents one of the few times my meager animation know-how was ever put to use, because I had to draw mouth movements and certain character and body part poses for the animator.” -ED

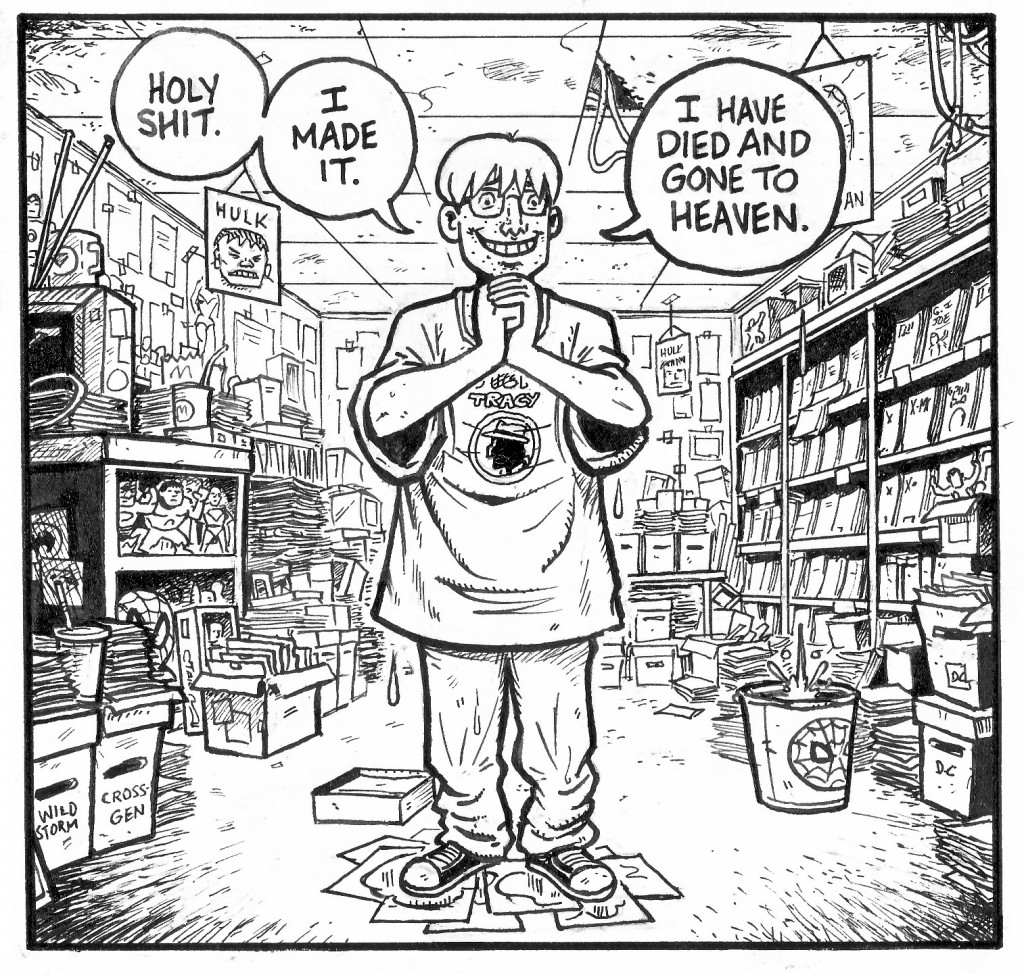

“Panel from an unfinished Eltingville Club strip I started in 2001 with a finished page and the art for two covers. I did a second page in 2002, and finished a third page in 2003. Haven’t worked on it since for various reasons. The idea was to do two more strips as a one-shot, retire the characters and collect all the Eltingville stories into a book. I still hope to do that, but I have no idea if it will ever happen.” -ED

“Trying to learn to draw the Simpsons. Working characters out on tracing paper for page 5 of the Treehouse story I’m drawing. There’s a lot of characters in the script and I’ve never drawn any of them more than once except Bart, Milhouse and Lisa. I’ve penciled over 40 characters by page 6, it’s driving me nuts. I want to punch the writer in the goddamned face, but unfortunately, I wrote it.” -ED

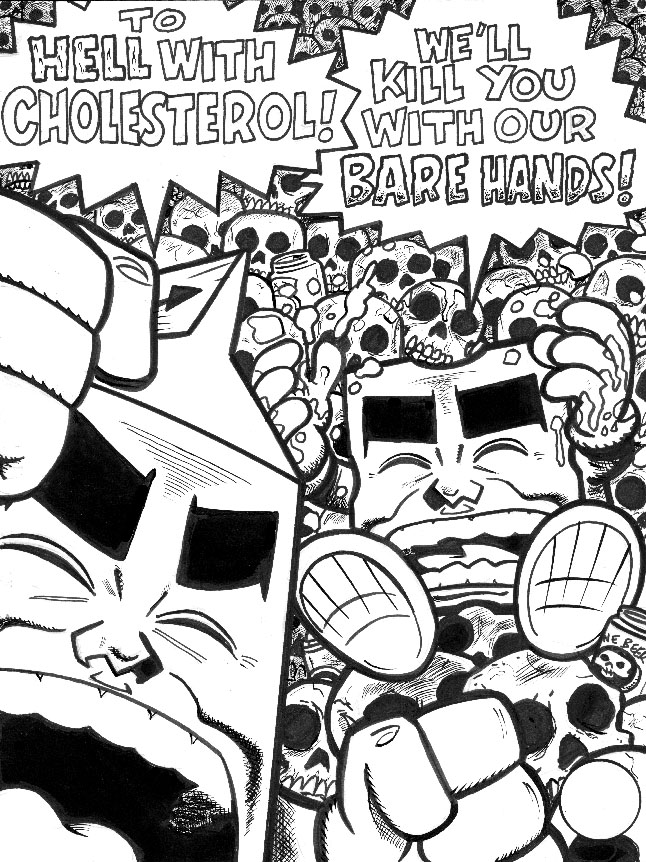

“A recent Milk and Cheese pin-up where they do what they do.” -ED

Thanks to Evan Dorkin for taking time out of his hectic schedule to answer my questions with incredibly sincere and in-depth answers.

Josh Jones

josh@comicattack.net

Hmm…I don’t know much about his work personally, but I once worked with a guy who really liked Milk and Cheese.

Josh, congrats on landing such a great interview subject. Dorkin is a hell of a talent and deserves all the attention he can get.

Josh, amazing work man. And props to Evan for being so candid.

Great interview and, as always, great interview subject. Evan is one of the most underused and most entertaining creators we have. Between Milk and Cheese, Eltingville and Space Ghost CtC alone, he should get a medal. the guy is just too freaking funny.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Artist of the Month: Evan Dorkin -- Topsy.com

Great stuff JJ. Working on STAS and Space Ghost sounds like a blast!

Pingback: Comics A.M. | The comics Internet in two minutes | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

Somehow I got an issue of Pirate Corp$ when I was a teenager and loved it, but could never find any other issues. I still have it. Is there a collected edition anywhere?

Pingback: 2010 Eisner Award Winners

Pingback: Indie Watch 11/23/2011 « Why Not Indie?

It would be nice if a TPB of the Eltingville stories ever shows up at all. I noticed somewhere in the world a Spanish edition was put out some years back.

http://www.amazon.com/Eltingville-ciencia-ficcion-fantasia-Eltingvilles-Science/dp/8478337520