I’m on the fence about character death in comics. At times, it infuriates me…particularly when it’s used for shock value. In those cases, it’s tasteless, usually graphically violent, and in the long run, hurts the credibility of the comic.

While certain writers (like Robert Kirkman, when he writes Walking Dead) can successfully present a story where “no one is safe,” killing too many characters without cause will eventually wear away the impact of the successive deaths. Ideally, when a character dies, the reader appreciates what the character has done to advance the plot, and will accept that his/her death was either a long time coming, or “worth it,” a necessary event to move things along further.

Spoiler Warning: The following paragraphs contain spoilers for DMZ #56, and that series as a whole. You have been warned.

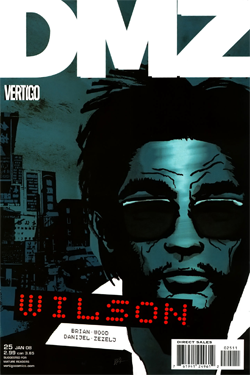

This past week I had the chance to catch up on one of my favorite series, Brian Wood’s DMZ. As a journalist, I tend to like stories that involve my profession, like Warren Ellis’s Transmetropolitan. Within this issue, a character named Wilson, who had been involved in the story since the very beginning, was killed by a missile strike by the US Army in the middle of New York City’s Chinatown.

This past week I had the chance to catch up on one of my favorite series, Brian Wood’s DMZ. As a journalist, I tend to like stories that involve my profession, like Warren Ellis’s Transmetropolitan. Within this issue, a character named Wilson, who had been involved in the story since the very beginning, was killed by a missile strike by the US Army in the middle of New York City’s Chinatown.

And it did not anger me one bit. I did not put down the issue, angry at Brian Wood for killing one of my favorite characters. I did not jump on the Internet to yell at him via Twitter, or post on a message board proclaiming he was a hack. Instead, I sat back, smiled, and thought “He died a good death.”

Wilson is one of my favorite characters in DMZ due to the duality of the character. When he’s introduced to the reader, we assume he’s a kindly old Chinese man who has taken pity on the series’ protagonist, Matty Roth. Roth is new to the war zone of Manhattan, and at that point in the series relies on many people to keep him from getting killed. Wilson is the first look the reader gets into someone who still lives somewhat of a “normal” life in the zone; he shares his beers with Matty, maintains a normal house, and seems quite well-adjusted.

However, hints start being dropped that the first impression of Wilson is a false one; he possesses numerous “grandsons” which show up at numerous times in the series. They have been errand boys, escorts, and bodyguards for Matty Roth, following Wilson’s orders with reverence and respect. Roth eventually starts piecing things together, noting, “Jesus, Wilson. How many grandsons do you have?” Wilson replies with a dismissing laugh, and the reader is left to think about the extent of his role in the scheme of things.

Wood enjoys taking the reader away from the main plot of DMZ every once in a while, and it is through one of these one-shot issues we learn the true extent of Wilson’s power: he runs and leads Chinatown in their efforts to “close up shop” and let the war play itself out.

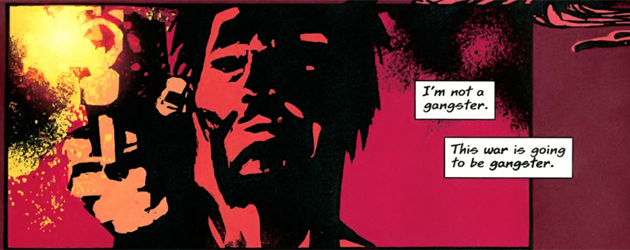

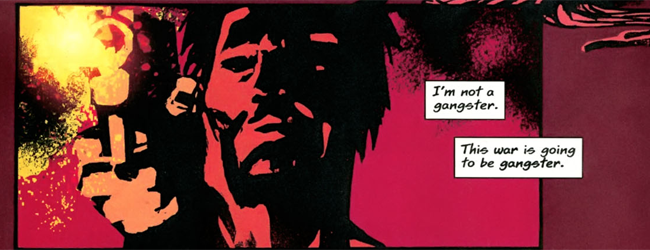

Once a common gangster, Wilson used the chaos of the war between DMZ’s “Free States” army and the US government to eliminate his higher-ups and take control of Chinatown. Realizing that his territory will need to survive until the end of the war, Wilson orders his people to close up shop; Chinatown would not welcome outsiders. He sends a message to the outside world: “leave us alone.”

Throughout the story, Matty treats Wilson as both a confidant and safe haven. Besides his close friend Zee and colleagues within his work, Wilson is the closest thing that Matty has to normalcy within the zone. My favorite issue of the series, “New York Times” (issue #12), explains this well. The issue is laid out as Roth’s notebook and guide to the zone: produced in the style of a zine/field guide, you can see Roth’s scrawled notes and candid observations.

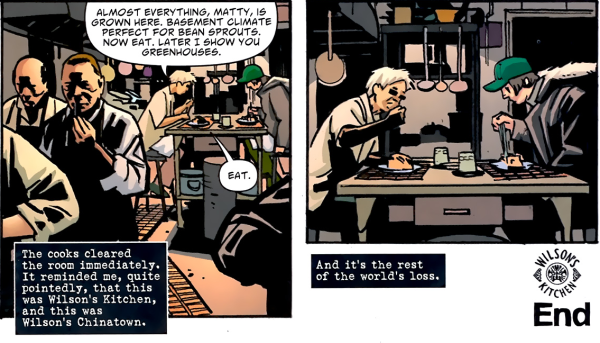

Within his section about Chinatown, he notes how Wilson took him to a wedding within the zone, partly to get him to take photographs for free. Roth notes that this was the safest he’d felt since he’d entered the war zone, and with good reason.

As we come to find out, Wilson has been sitting on one of the largest pre-war gold stockpiles in New York; urban legends have been spun around the “Chinatown Gold,” and this substantial financial base has been backed up with even more cash. Within Wilson’s issues, we see him unpacking tanks and helicopters, preparing to defend his territory by any means necessary. Conversely, we see him maintaining blocks-long kitchens, providing healthy food, at least to him and his close circle.

Wilson represents an aura of safety whenever he enters the story; his presence gives the story a chance to wind down and let the reader stop worrying about the hazards of the location where exposition might be taking place. Having a conversation in the middle of a street covered by snipers, or a building being bombarded with shells, takes away from the plot, as the reader is wondering, “Who’s going to get shot next?” Wilson’s Chinatown lets us think, “Alright, Roth is safe here. Let’s pay attention to what’s being said.”

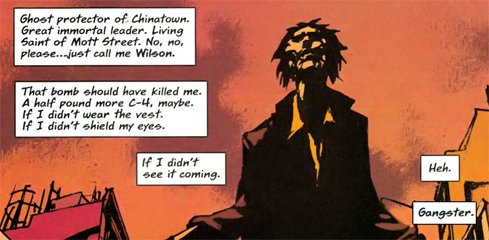

What drew me to Wilson’s character, however, was even though he had the potential to be a stereotypical classless thug, he is not without honor. He genuinely cares for Matty, his grandsons, and most importantly, Chinatown. He is ruthless when he has to be, but is not above sending a message by doing nothing. An example of this is where he takes a half-pound of C4 to his (flak-jacketed) vest, opting to say (without words) that “you cannot kill me.”

What drew me to Wilson’s character, however, was even though he had the potential to be a stereotypical classless thug, he is not without honor. He genuinely cares for Matty, his grandsons, and most importantly, Chinatown. He is ruthless when he has to be, but is not above sending a message by doing nothing. An example of this is where he takes a half-pound of C4 to his (flak-jacketed) vest, opting to say (without words) that “you cannot kill me.”

However, this was not to be. Ultimately, this kind of life leads to certain dangers; after a small nuclear explosion goes off in the DMZ, the US Armies are less hesitant to, bluntly, bomb it until it’s flat. In the story’s current arc, “Collective Punishment,” the story line deals with the residents of the zone dealing with constant bombardment, and this includes Chinatown.

After years of their “leave us alone” strategy working quite well, the bombs are no longer being aimed at any specific area; the army is looking to raze the DMZ as well as it can, Wilson is now forced to consider the well-being of the population of Chinatown, and that maybe it’s time to give up.

Sending the families (including his grandsons) out of the zone for their own safety. Eating in his restaurant with a loyal bodyguard (who has no family of his own), a missile hits the ground, failing to detonate. It cartwheels down the street, eventually crashing (and exploding) through the restaurant’s window, bringing to an end the career of the Ghost Protector of Chinatown. His death, glorious as it is, brings to an end one of the one true “safe” zones for the protagonist to convene, and hopefully signals that the entire plot of DMZ may be coming to a close.

So let’s raise a glass to Wilson, who showed us that through great writing and pacing, gangsters can have honor, minor characters can be as (if not more) interesting as the main hero, and that death in comics doesn’t always have to happen on a two-page spread with someone’s face being pushed out the back of their skull.

Matt Demers

contact@comicattack.net

Good stuff Matt!