Welcome to Comics Are My Religion, a look at theology through the lens of comic books. There are some basic ground rules about engaging in respectful dialog about religion in this column. There be spoilers ahead, so beware!

A few Sundays ago, I led my first adult Sunday School class on a comic book. Currently, in our lectionary, which is a three-year cycle of Scripture readings, we are going through the Exodus story. One thing that has always troubled me about this epic story is the role that the Pharaoh plays. Yes, every story needs a villain, and Exodus is no different.

Historians have argued about who the Pharaoh of the Exodus actually was, but in most popular culture, Pharaoh is characterized as Ramses II. Reading the actual story, the biblical writers never clarify a distinction between the Pharaoh who declares that the male Hebrew babies should be killed, and the Pharaoh who refuses to release Moses’s people at his bequest. Pharaoh’s identity in Exodus really isn’t the point, as he really becomes a placeholder for all oppressive governments and systems. But what is most difficult to understand about the Pharaoh’s role in Exodus is his motivation for being so stubborn.

Historians have argued about who the Pharaoh of the Exodus actually was, but in most popular culture, Pharaoh is characterized as Ramses II. Reading the actual story, the biblical writers never clarify a distinction between the Pharaoh who declares that the male Hebrew babies should be killed, and the Pharaoh who refuses to release Moses’s people at his bequest. Pharaoh’s identity in Exodus really isn’t the point, as he really becomes a placeholder for all oppressive governments and systems. But what is most difficult to understand about the Pharaoh’s role in Exodus is his motivation for being so stubborn.

Exodus 4:21 says, “And the Lord said to Moses, ‘When you go back to Egypt, see that you perform before Pharaoh all the wonders that I have put in your power; but I will harden his heart, so that he will not let the people go.'”

The Lord becomes the initiator of Pharaoh’s stubborn nature, which opens up a host of questions for the reader: If the Lord wants freedom for the Hebrews, why make it so hard for them? Does Pharaoh get a choice at all in the matter? Is the real villain here the Lord? If so, why use Pharaoh so cruelly? Does Pharaoh have any self-determination at all?

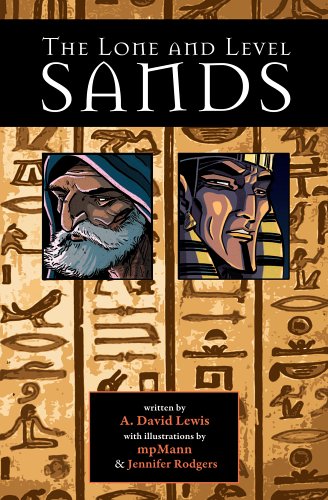

These are questions that A. David Lewis and mpMann address in 2005’s The Lone and Level Sands published by Caption Box and Archaia. This is the book I used in my adult Sunday School class to address these very ambiguous questions.

The Lone and Level Sands focuses on the Exodus story from the perspective of Ramses II. Much like the 1998 animated film The Prince of Egypt, The Lone and Level Sands attempts to fill in some gaps in the story, fictionalizing the relationship between Ramses and Moses, and fleshing out Ramses’s motivations a little more clearly.

The book begins with Ramses greeting his father, the Pharaoh Seti, after a battle against Egypt’s enemies. Ramses soon reports to his father that Moses has killed an Egyptian slave master, which is Moses’s reason for leaving Egypt. Years pass, Ramses becomes Pharaoh, and Moses returns, speaking cryptically for his god named Yahweh.

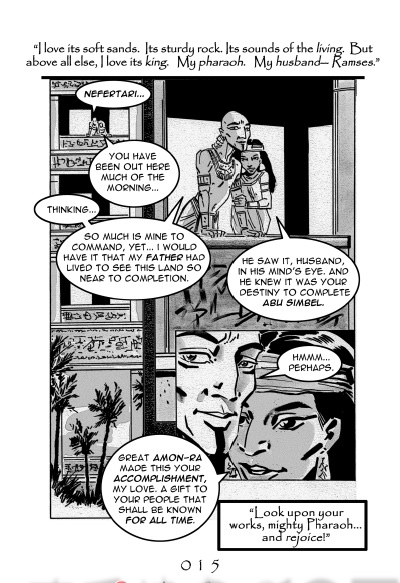

Ramses is characterized as the beloved king, who is even respected by the ambassadors of rival countries. He has set up a strong house of his own, with many wives, advisors, and spiritual guides. However, once Moses begins to show up, things begin to fall apart for Ramses.

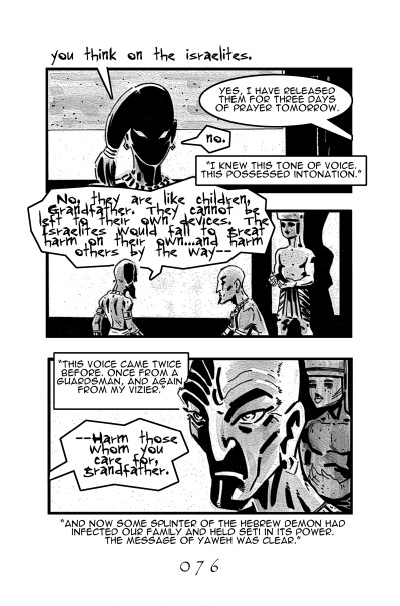

What’s most interesting to me about Lewis’s depiction of this story is that his reason for Ramses’s hardened heart is a mysterious voice that only Ramses can hear. The voice comes from the mouths of people around him, as if they are possessed. He hears this voice from a guard, his vizier Ta, his son Seti, and his comatose wife Nefertari. The voice comes at times of great decision for Ramses, as to whether or not he should let the Hebrews worship their god in the wilderness. Much like the biblical narrative, Ramses goes back and forth on decisions. On one hand he relents due to the personal suffering brought to him by the many plagues. On the other hand, he is quickly convinced to hold onto the Hebrew slaves. Lewis’s book creates this duality in Ramses as well, but using this mysterious voice as the catalyst for his hardened heart.

What’s most interesting to me about Lewis’s depiction of this story is that his reason for Ramses’s hardened heart is a mysterious voice that only Ramses can hear. The voice comes from the mouths of people around him, as if they are possessed. He hears this voice from a guard, his vizier Ta, his son Seti, and his comatose wife Nefertari. The voice comes at times of great decision for Ramses, as to whether or not he should let the Hebrews worship their god in the wilderness. Much like the biblical narrative, Ramses goes back and forth on decisions. On one hand he relents due to the personal suffering brought to him by the many plagues. On the other hand, he is quickly convinced to hold onto the Hebrew slaves. Lewis’s book creates this duality in Ramses as well, but using this mysterious voice as the catalyst for his hardened heart.

Stylistically, mpMann depicts this voice with scratchy and scribbled, almost sinister, letters. The one through whom the voice speaks becomes dark and shadowed, as if a haze of black lines covers them. Upon reading the book for the first time, I immediately suspected the voice to be the voice of Yahweh, as even Moses is first shown as the voice’s avatar. However, Lewis and Mann make this extremely ambiguous, making us wonder if the voice is simply a voice in Ramses head, or the divine voice of Yahweh, or perhaps even the voice of Ramses’s god, Amon-Ra. Lewis leaves this question up to the reader, which allows our own imaginations to continue the debate that Exodus originally sets up.

The voice gives reasonable cause for Ramses to remain hardened. To release the Hebrews would cause damage to them and to the Egyptian people. As primary protector and semi-divine being, Pharaoh must take responsibility for these people in order to continue his successful reign. However, as the story continues, that hardness of heart only serves to chip away at all things that Ramses holds dear–his friends, his family, his army, and even his kingdom.

At the end, as Ramses has seen the Hebrews cross the Red Sea, and all of his men have been destroyed, he strips himself in the desert sand and screams to the heavens: “ENOUGH! What more would you have of me? I have played my role! My land, my family, my people–we have paid the price slated for us! Is it over? Why do this? What sick pleasure comes from our suffering? Revenge for the Hebrews? Sheer entertainment? You could have freed them without harm to us! You could have prevented their enslavement in the first place! Damn you, why? I am mortal. I never thought otherwise, never believed the priest’s declarations! If the divine truly chooses the Hebrews, then I have no recourse. I never have. Then why…why manipulate me so?”

At the end, as Ramses has seen the Hebrews cross the Red Sea, and all of his men have been destroyed, he strips himself in the desert sand and screams to the heavens: “ENOUGH! What more would you have of me? I have played my role! My land, my family, my people–we have paid the price slated for us! Is it over? Why do this? What sick pleasure comes from our suffering? Revenge for the Hebrews? Sheer entertainment? You could have freed them without harm to us! You could have prevented their enslavement in the first place! Damn you, why? I am mortal. I never thought otherwise, never believed the priest’s declarations! If the divine truly chooses the Hebrews, then I have no recourse. I never have. Then why…why manipulate me so?”

Ramses’s questions become ours as we wrestle with the Exodus text.

The Lone and Level Sands gives no easy answers, and perhaps there aren’t any. Life continues with struggles–earthquakes, hurricanes, wildfires, terrorism, famines, wars, racism, hatred, violence–what part do we play? Do we have free will to make choices about the course of our lives, or does God originate the hardness of our hearts? It is not such an easy question to answer.

In our adult Sunday School class I also left that answer ambiguous. Some will say it’s not for us to answer at all, we are just called to have faith. For others, this is a stumbling block where people find no comfort and end up walking away from religion altogether. I fall into the camp that this is a mystery, one that we should wrestle with, poke, prod, and study. We should never be satisfied with the ambiguous answer from Scripture. Instead, we can use our imaginations like A. David Lewis and mpMann do so well with The Lone and Level Sands to fill in some blanks and raise even more questions. It’s ventures like this that make religion worth studying and comics worth reading.

Jeff Jackson

jeff@comicattack.net