Welcome to Comics Are My Religion, a look at theology through the lens of comic books. There are some basic ground rules about engaging in respectful dialog about religion in this column.

The study of religion and comics is growing. In the last few years, more books have been published on the subject. People are actually studying the connection between the two as an academic discipline. At the forefront of the discussion is A. David Lewis, a Ph.D. candidate at Boston University and comic book creator.

The study of religion and comics is growing. In the last few years, more books have been published on the subject. People are actually studying the connection between the two as an academic discipline. At the forefront of the discussion is A. David Lewis, a Ph.D. candidate at Boston University and comic book creator.

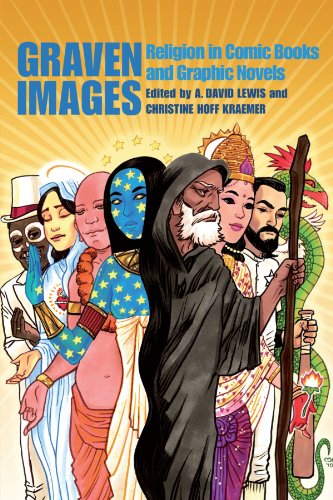

David contacted me which began a conversation about the field of religion and comics, which turned into this interview. He most recently co-edited and published a book called Graven Images: Religion in Comic Books and Graphic Novels. In the following conversation, we just scratch the surface of what is going on in the study of religion and comics.

Jeff: OK, origin time: Tell us first about your background in comics and academia.

A. David Lewis: Until relatively recently, my academic background has been fairly traditional. I got my B.A. in English & Psychology, then I earned my M.A. in English Literature from Georgetown University. It was during my time in Washington, DC that I began writing articles and presenting papers that examined comics from a number of perspectives. By the time I moved back north to Massachusetts to pursue my Ph.D. at Boston University, I had already immersed myself in the growing world of Comics Studies–the various journals, conferences, and scholars who had already begun pioneering the field.

JJ: Those are some pretty impressive credentials. What first drew you to comic books?

ADL: I was a voracious reader as a kid, and my parents made sure I was well-stocked in all manner of books. Included among them were comic books, I’m pleased to say, so I had the opportunity to enjoy them alongside prose novels. Even at a young age, I saw an interplay between the “literature” I was reading (e.g. The Hobbit, A Wrinkle in Time) and the comic book material. Additionally, the comics appealed to my youthful imagination a great deal, whether it was superheroes, G.I. Joe comics, or comic strip collections (e.g. Bloom County, Calvin & Hobbes). So, in all, I feel as though comics have been part of my appreciation for language and storytelling since the very beginning.

ADL: I was a voracious reader as a kid, and my parents made sure I was well-stocked in all manner of books. Included among them were comic books, I’m pleased to say, so I had the opportunity to enjoy them alongside prose novels. Even at a young age, I saw an interplay between the “literature” I was reading (e.g. The Hobbit, A Wrinkle in Time) and the comic book material. Additionally, the comics appealed to my youthful imagination a great deal, whether it was superheroes, G.I. Joe comics, or comic strip collections (e.g. Bloom County, Calvin & Hobbes). So, in all, I feel as though comics have been part of my appreciation for language and storytelling since the very beginning.

JJ: I really identify with that. You and I had some similar tastes in literature and comics as kids. So tell us about the book you recently published, Graven Images: Religion in Comic Books and Graphic Novels.

ADL: Graven Images is the brainchild of both Christine Hoff Kraemer and myself from discussions we’d had while both at Boston University. We knew that there was a lot of untapped interest out there in how religion and comics interplayed. There had already been some books released that related to the topic, but often they focused on a particular religion or religious history. Fortunately, neither Christine nor I had a particular agenda or philosophy that we needed to promote. Rather, we were just hungry for the discussion–good, bad, and ugly.

JJ: The concept is relatively untapped, with the exception of a few books, so I was glad to see you tackle it on such a wide scale and gather folks for the conversation. Who are some of the creators and scholars that wrote essays for the book?

ADL: Of the creators, Mark Smylie (creator of Artesia and Archaia Studios Press founder), G. Willow Wilson (creator of Air, upcoming writer of Marvel’s Mystic), and Saurav Mohapatra (writer of Virgin Comics’ Devi and The Sadhu: The Silent Ones) all wrote pieces for the book, all of which were excellent. These are smart people in their own right, so they didn’t require extensive footnotes or academic mumbo-jumbo to convey some really thoughtful ideas. The “proper” scholars involved ranged from religions and disciplines from all of the world, in fact!

Oh, additionally, Douglas Rushkoff wrote us a sensational introduction, and Scott McCloud was kind enough to let us reprint some of his own blog observations in the book.

JJ: The book also includes essays written by scholars and comic fans, including Aaron Ricker Parks, Emily Taylor Merriman, Laurence Roth, Anne Blankenship, G. St. John Stott, Darby Orcutt, Andrew Tripp, Ericko Ogihara-Shuck, Mike Grimshaw, Julia Round, Clay Kinchen Smith, Kate Netzler, Kerr Houston, Megan Goodwin, J. Lawton Winslade, Emily Ronald, and Steve Jungkeit, which is a pretty impressive list. Give us a preview of the religious viewpoints represented. What new insights do you see coming from comics that shed light on a plurality of faith traditions?

ADL: What I most like about Graven Images is that we avoided having an agenda. The book has people talking about atheism on one page, neopaganism on another page, and Catholicism on yet another. Our goal as editors was to show that these conversations have something to say to each other and are not necessarily in any divisive opposition: We can learn interesting things from others that can inform or enrich our own beliefs. It’s worth saying, though, that we also avoid saying, “All religions are the same; all beliefs are equal,” because that would be disingenuous. If the essays and perspectives have anything in common it’s that (1) they’re fascinated by what comics can do and have done as a medium, and (2) they respect others’ rights to dissenting-but-thoughtful opinions. So, while a reader might be delighted to find an essay about Hinduism or soteriology, he or she will also be challenged to engage a variety of other viewpoints as well.

JJ: That’s the fascinating thing I find about the connection between religion and comics; despite the diversity of philosophical thought, faith tradition, or moral practice, comics have a way of adding new insight into the discussion, and you’ve shown that diversity well in Graven Images. The book actually developed from the conference of the same name. How did the Graven Images conference come about?

ADL: At the time, Christine and I had a lot of support from Peter Hawkins of the Luce Program at BU (who has subsequently moved on to Yale in the intervening years). Once we had a game plan as to the scope, date, location, and cost of a potential conference, we also received support from BU’s Department of Religion and the American Academy of Religion’s local chapter. After putting out feelers, we hooked James Sturm, comics creator and founder of the National Association of Comic Arts Educators (NACAE), as our keynote speaker and put out a call for papers. Christine and I had publication in mind down the line, but we first wanted it to be a quality conference with a variety of perspectives. (Due to the modest size of this inaugural conference, we had to limit it to English-language works in the American market.)

JJ: What was the response to the conference? Are more people now studying religion and comics as a discipline?

ADL: There was a good response, lots of enthusiasm, and, best yet, the participation of some other comics creators, namely G. Willow Wilson, Mark Smylie, Saurav Mohapatra, and Steve Ross (creator of Marked!). We felt it was a nicely well-rounded event with a lot of top-notch scholars sharing their excellent insights. I don’t want to give the impression that no one has ever thought of discussing religion and comics together in the same breath. But, this being the first university conference explicitly dedicated to it, it sort of planted a very visible flag. Such studies were less likely to be seen as a sideline but, instead, as an active part of lived religion in the U.S.

JJ: Are you finding a growing number of creators who are interested in talking about comics and religion as an academic discipline? Who are some creators you would like to get in on the conversation?

ADL: We were fortunate enough with the Graven Images conference to have top-notch creators like the ones I mentioned earlier all on hand and prepared to be part of the discussion. I think it’s on the tip of a lot of people’s tongues, if they aren’t already discussing it. The trick has been to engage the topics in a language that works for everybody: the Religion scholar, the Literature scholar, the Media Studies/Popular Culture scholar, the industry profession, the creative talent, and the readers themselves. So many people have viewpoints, thoughts, and anecdotes to relate; the issue isn’t generating interest but, rather, finding the best common ground without reducing it to the lowest common denominator or simplifying it so it results in weak sauce.

JJ: Good point. With this subject matter, it might be difficult to reduce it in an unhelpful way. What went into planning such a conference? Was it hard to find creators and scholars who shared your affinity for religion and comics?

ADL: The bigger challenge was geography, not interest, really. In fact, I think that if we held it in, say, Chicago or Los Angeles, the line-up of scholars and creators might have been somewhat different, but it would have been just as potent an event. Of course, being in Boston, a city loaded with schools, did help.

JJ: There is so much diversity in religion & comics, and with as many comics that embrace it with the intention of honoring religion, there are also a great amount of books out there that push the limits with their critiques of religion, which can create controversy. With books like Preacher, Chosen, & even Jesus Hates Zombies, do you think religion in comics is automatically controversial?

ADL: I don’t think there’s a built-in conflict or controversial element between comics and religion. But, like film, it’s a visual medium, and it invites spectacle. Unlike film, though, it’s far less policed and less corporately involved, so more extreme — and, yes, more sacrilegious — works can make it through to the market. Frankly, being sacrilegious isn’t a bad thing in and of itself; there can still be a great and entertaining story there. There can even be a useful message to or between religious communities. It’s when a work sets out to insult or persecute another group when the line must be drawn. Personally, I don’t think either Preacher or Chosen crosses that line. (Not sure how I feel about Jesus Hates Zombies…but perhaps he would!) For each one that rankles, I would also offer Blankets, MAUS, Persepolis, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and a host of other thoughtful works that address religion in what I feel is a non-controversial manner.

JJ: True enough, and the medium is wide to include both controversial books and non-controversial books. That’s what makes the connection between religion & comics so interesting and inspiring. What comics have inspired you the most in your study of religion?

ADL: Well, there’s a difference between “inspired” and “triggered thought.” That is, MAUS was probably the only comic book you could find in the library of our local synagogue or on the bookshelves of Barnes & Noble (in the days before there was an extensive Graphic Novels section). I also had seen some of R. Crumb’s stuff that was positively irreverent of religion; it sort of flew in the face of some of the “comic book” Bibles I had seen that were so straight-laced. So, I knew the whole relationship was there, even from a young age. But it really wasn’t until I read the entirety of Sandman as well as Kingdom Come that I started to become intrigued about some scholarly relationship between the medium and the topic. [Neil] Gaiman’s words and [Alex] Ross’s art inspired me to think about it analytically.

JJ: There really are a host of books that have opened up the discussion between comics and religion, without really meaning to. What comics are you currently reading that you think make some good connections to religion?

ADL: I was really enjoying G. Willow Wilson’s Air until its recent cancellation. I’m also giddily looking forward to Craig Thompson’s Habibi later this year.

JJ: I haven’t read Air, so I’ll take that as a high recommendation. I loved Blankets, so anything Thompson does, I’ll read. Despite these excellent works, comics haven’t traditionally been held as “scholarly works.” What do you think is changing that mindset today?

ADL: Partially, I think it’s a generational shift. The same film executives who grew up on comics and, in turn, have been making them into movies graduated alongside the rising professors at colleges nationwide. Also, comics have moved from either a fringe readership or a speculator’s market to genuine money-making vehicles and realms for social commentary. (They’ve long been such realms, but fewer people were “listening” in the ’70s than in the conventioneering ’90s and the Internet-wired 21st century.) Overall, even if other scholars look down their noses at the content of the comics — some of which is, yeah, lousy, but that’s true of any medium — they cannot deny that it’s having cultural, artistic, and historical impact.

JJ: That’s really true of comics being accepted across the board as well. But I think what people are discovering more and more is that comics communicate differently than any other type of media. How does sequential art communicate ideas of faith and religion in ways that other types of media might not be able to do?

ADL: Hm! Well, I’ve toyed with at least one idea along these lines. I think sequential art depicts both Time and Eternity in a way no other medium can. I’m currently writing a piece that explore this, but, to paraphrase myself in short: Eternity can be glimpsed in the layout of every comic book page because, when we read comics, we cheat. Neurologists studying eye movement while reading comics have the data to prove it. We look ahead however quickly and spy the layout to come. This combination of reading comics panel-by-panel while also, out of the corner of our eyes, peeping at the overall design of the page is the hint of Eternity. Sequential, chronological Time can still unfold as expected as readers move from panel to panel.

JJ: So would you say there’s a scientific reality to how we read comics and how that connects to our understanding of the world, our place in it, and the things we consider sacred?

ADL: I’m not sure I would call it a “scientific reality,” per se, but I do think that reading a comic is actually a very complex act, and I think that the complexity of that act can be usefully connected to the complex way in which humans experience Time and understand Eternity. Moreover, yes, the way creators and readers invest meaning in a story can also be likened (without too much metaphor) to how humans find meaning in sacred acts, texts, rites, and stories. I think all of this has more to do with the human mind–whether biologically or spiritually–than with some divine predisposition of the comic book medium, though. Said another way: I think comics, in many cases, engage a wide array of our mental abilities, some of which we usually reserve for engagement with religious and sacred experiences.

JJ: Exactly! This is what makes comic reading and the connection to our biology and spirituality exciting to me. Perhaps that’s something that can be explored more fully at another conference. Are there plans for a future Graven Images conference?

ADL: Tentative plans, yes, but plans just the same. It’s likely to happen some place other than in Boston, but that location is still up in the air. Part of my hope is that, in addition to the scholars already involved, others might read Graven Images or read this coverage and contact me, expressing an interest to help take part in its future planning.

JJ: I know I would love to be in on the next conference! I know also that you are quite an accomplished creator yourself in addition to the Graven Images work you’ve done. What other books have you published?

ADL: On academic topics, I’ve been published in The International Journal of Comic Art, The Journal of Popular Culture, The Encyclopedia of Comic Books & Graphic Novels, and upcoming collections from Sheffield Pheonix Press, Oxford University Press, and the Sequart Research & Literary Organization. But, in terms of complete books, I’ve written and co-written graphic novels including Mortal Coils: Bodylines, The Lone and Level Sands, and Some New Kind of Slaughter.

JJ: I will definitely be looking at those for future Comics Are My Religion columns. You were recently on WBUR, Boston’s NPR affiliate, talking about Islam in comics. Tell us about the growth of Islam in comics.

ADL: In short, Muslims were largely overlooked in superhero comics much before the 1980s. There were generic “Arabs,” and rarely were they more than caricatures or cannon fodder. As the Middle East began to appear more and more often in the U.S. media, superhero publishers began to gradually introduce a few Muslim characters here and there, though they were still poorly defined and largely tokenistic. As you might image, after September 11, 2001, every form of media needed to look at how it engaged Islam, and U.S. superhero publishers were no exception. Very few Muslim supervillains were presented, but, rather, much of the U.S.’s tension with Islam was reflected in how the traditional superheroes interacted with new allies like Dust of the X-Men or, more recently, Nightrunner in Batman. The subtext and “conversation” is slowly becoming more sophisticated, though a number of stereotypes still remain, obviously.

JJ: There’s a subject that I want to learn more about. As a Christian, I would love to have a Muslim perspective represented in this column. If there are any Muslim readers out there who want to give us that perspective, please e-mail me!

Thank you, David, for giving us an insight into this wider world of religion and comics. Folks who want to follow up with him can contact him through his website www.captionbox.net.

Everyone can also pick up Graven Images: Religion in Comic Books & Graphic Novels at Amazon.com along with the rest of his publications.

And be sure to check out more of my work on Comics Are My Religion here on Comicattack.net!

Jeff Jackson

jeff@comicattack.net

Pingback: Comics Are My Religion: The Apocalypse Plan

Pingback: The Lone and Level Sands : Saint Nicholas Episcopal Church - Hamilton Georgia