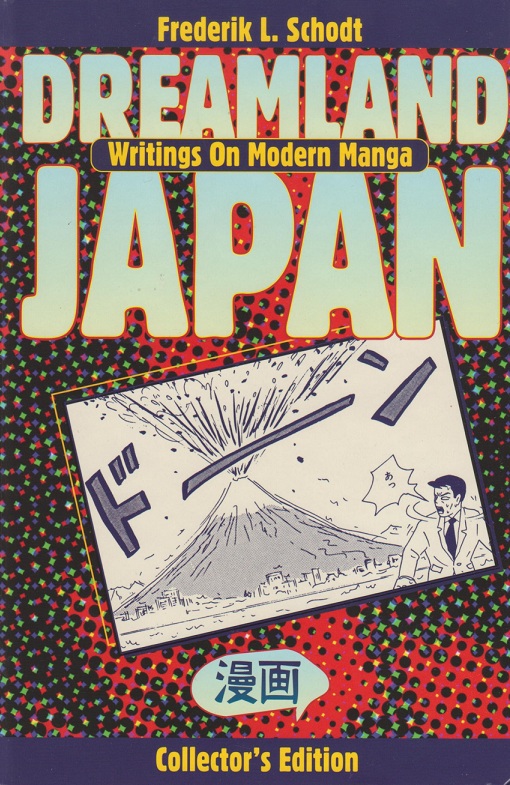

Title: Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga (Collector’s Edition)

Title: Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga (Collector’s Edition)

Author: Frederik L. Schodt

Publisher: Stone Bridge Press

Price: $29.95 (HC, 375 pages)

Vintage: Originally published in 1996, current version in June 2011

Written during the mid-90s at the height of the manga boom, reading Dreamland Japan is like looking through a window at manga’s past. The industry has come a long way since, and also regressed a bit since. The book is an excellent look into the artistic culture of Japan, as well as consumerism culture and Japan’s social growth. Reading this book you can learn a lot about Japan’s cultural, social, and political environment, though as its focus is solely on how those things relate to manga, it certainly is in no way a definitive text on any of them. Schodt’s personal knowledge of the industry still makes for a very informative read. This book isn’t written by some random person tasked with writing about a subject they know little personally about, but rather a man with real knowledge of the industry and the people who have played a large role within it. It’s obvious Schodt knows what he’s talking about, and has not only researched well, but has intimate knowledge to share. I think Schodt comes off a bit strong at times in the text (often quite forward, and at times almost insulting), but the conversational style of the book makes it an easy read.

Here’s what you can expect to find in Dreamland Japan:

A very brief history of manga. Part of what you’ll find focuses on the artistic progression of manga, while the other focuses strongly on the culture of manga, with emphasis on amateur dōjinshi conventions like Comic Market. If you’ve ever wondered what the big deal is about these seasonal, gigantic conventions, Schodt readily fills you in on their history and their impact on the commercial manga market. Schodt also follows the progression of artistic style, and notes the western influence on manga’s panel format and some artistic styling.

An extensive look at the major manga publishers and the manga magazines they were publishing in the mid-90s, covering most, if not all, the major genres. From shōnen magazines to pachinko magazines, boys’ love magazines to magazines for yankī (girl gang members, particularly those interested in motorcycles and cars) mothers, Schodt discusses their founding, sales history, target audiences, standard content, and other various aspects. Each magazine mentioned comes along with a standard cover image and a table delineating circulation numbers, price, page count, founding, publisher, standard dates of publication, and physical format design. This is not a market we really have in America, so it’s an intriguing glimpse into Japan’s publishing houses and purchasing culture. There are hundreds of these serialized manga magazines in Japan; I think we’re down to one here in America, that is still physically printed (Yen Plus, for example, has gone digital only).

A lot has changed since this book was written, but a lot has also remained the same, and even the nature of the changes is similar. The same censorship issues, attacks on erotic works, and so on, are repeating again today. Reading this book with a knowledge of the current industry reveals a cycle of government interference, and if it follows the previous pattern, what’s taboo today will be fine again after some time, then taboo again at another time.

A quite extensive look at various manga creators follows, most personally known by Schodt. As Schodt warned at the beginning of his book, I don’t recognize many of the artists he mentions here. I am, however, happy to note that some of these artists have gained notoriety since this book was originally published; namely Shigeru Mizuki, whose Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths was published in America this year. Also mentioned is Akimi Yoshida’s Banana Fish, much loved and thoroughly dissected by the lovely ladies at Manga Bookshelf. With each artist, Schodt goes into a small biography, and then describes several of their best or most influential works. What I really got out of Schodt’s section devoted to a plethora of talented manga artists, was just how much incredible work is out there that we’re not getting in America. Time to go bug some publishers, I think. Anyone want to publish King of Editors by Seiki Tsuchida? It sounds a lot more interesting than Bakuman. Digital Manga, I would love to read Wakuni Akisato’s Tomoi. I think Kaiji Kawaguchi’s Silent Service could be relevant again (though it’s a big risk at 32 volumes). Or how about some delicious gender bending in the Asuka Era historical tale Emperor of the Land of the Rising Sun? After how much I’ve been loving Ōoku The Inner Chambers, I can see myself enjoying Reiko Okano’s Fancy Dance.

After his extensive look at favorite and influential manga creators, Schodt devotes an entire section to the God of Manga, Osamu Tezuka. If that name, at the very least, doesn’t sound familiar, you can’t consider yourself a manga fan. That would be like claiming to be a fan of musicals without knowing who Gilbert and Sullivan are, or a fantasy fiction lover without recognizing Tolkien’s name, or a film buff without any knowledge of the works and impact of Orson Welles. The section is well detailed and informative. Again, this is a creator whom Schodt personally knew, and indeed seems to have spent a good deal of time with, which lends to an intimate look into the life of one of the most famous people in Japan. This section does, however, read as if it is a collection of short pieces originally published separately, and then bound together for this book, as there is a good bit of unnecessary repetition.

The next section, “Beyond Manga,” discusses manga’s transition to other media, specifically film. The section appropriately begins with a look at world famous animator Hayao Miyazaki, with a focus on his manga and film Nausicaa. After an in depth look at erotic manga artist and filmmaker Takashi Ishii, the chapter shifts to talk about novel writers. Schodt describes, in detail, the various types of industry authors and how they’re viewed in the industry, such as: manga creators who also write novels, novel writers who also write for manga, those who completely quit one side and went to the other, etc. Schodt touches on specific authors, and describes the modern evolution of novels in Japan, their influence on manga, and manga’s influence on novels. He even devotes a section to educational manga, or the use of manga to create engaging informative works. Examples would be creating product manuals with manga illustrations, emergency pamphlets drawn as short manga comics, or government endorsed pamphlets that reach more citizens with engaging illustrations. He goes on to explain how manga has been affected by technological advances like computers and the Internet, highlighting specific creators like Buichi Terasawa, and discussing the advantages of digitizing comics.

The last chapter is “Manga in the English-Speaking World,” and is more familiar territory. Schodt first gives us a crash course on the state of manga around the world, before diving into a more in depth look at manga in America. Provided here is a brief but informative history of manga publishing in America (up until the mid-90s of course, so it just misses Tokyopop, which was founded in 1997), focusing on Dark Horse and Viz Media, who are still around today. There is also an overview of manga oriented magazines, most of which are no longer around. A lot has changed in the industry since Schodt wrote his book, and that is most clear in this section of the book. Manga publishing companies have both risen and fallen since (especially recently, as companies have been folding left and right), magazines have begun and ceased, and stores that once shunned manga have started devoting space to them (while other dedicated stores, like Suncoast, have nearly vanished). The only manga magazine (publishing serialized manga) that I can think of that is still around today in physical print is Viz Media’s Shonen Jump. Their Shojo Beat magazine ceased publication in 2009. Yen Press’s Yen Plus magazine ceased its print run in 2010 and now publishes its magazine solely online. For magazines focused on manga and anime entertainment, I can think of only one that remains in print, and it is quite young. Protoculture Addicts ceased regular publication in 2009, Newtype USA in 2008 (it then became PiQ, which only ran for four issues), Anime Insider in 2009, and Animerica in 2005. As far as I know, only Otaku USA remains, a bimonthly magazine that began in 2007. The last part of this chapter focuses on American fandom, starting with a look at the first official American anime/manga convention, AnimeCon ’91 in California. There are many more conventions today, spanning not only all across America, but the entire globe; and in contrast to the conventions of this book’s time, they are increasingly populated by a growing female fanbase. The Internet, which was just becoming widely used at the time of the book’s original publication, is now vastly populated with all manner of otaku related websites. Manga can now be read in abundance (both legally and illegally) on a plethora of websites, and anime shares a similar viewing growth. Merchandise that could once only be found at conventions, if you were lucky, can now be purchased from a sea of websites. Fan communities have exploded all over the ‘net, industry news from inside Japan can be easily found, and fans can even follow their favorite creators on sites like Twitter. The presentation of this technology in Dreamland Japan is humorously archaic, as technology and the use of the Internet has come a long way since Schodt researched for this book. It is also a bit prophetic, as Schodt ends one chapter with: “Inevitably, as anime and manga become more and more mainstream, this dark side [referring to erotic manga, and particularly the “Lolita” genre] of the phenomenon will invite more and more criticism.” And indeed it has; only just today I saw an article through the CBLDF about a man whose computer was seized at the American-Canadian border (crossing into Canada), and who is being charged with possession of child pornography with intent to import it into Canada.

The afterword in Dreamland Japan is one of its new features, and was written by Schodt for this edition of the book. Here, Schodt makes note of the changes that have occurred in the industry since he first wrote this book, like the enormous growth of manga up until about 2009, when it seems to have imploded somehow, despite the rapid increase of manga and anime fans. In contrast to the hopeful, struggling but slowly growing industry of the early-mid-90s, this section paints a more realistic, almost bleak picture. The essential reality is that nothing can boom forever; eventually the industry had to hit a wall. It’s not all about America, of course, as Schodt also provides a look at the current state of the manga/anime industry in Japan, which has also declined. The blame is placed on the changing culture, the changing population demographics, a slow economy, and even globalization (in relation to censorship from outside influences). Censorship from both inside and outside Japan is an important topic quite recently discussed in the media, and Schodt touches on it here briefly, but it’s an entirely separate thing to discuss that could make up its own book. A portion aptly titled “The Internet Giveth and the Internet Taketh Away” discusses the growth of American fandom and the increasing use of the Internet, which has both helped and harmed the industry. Aside from the obvious (fansubs and fanscans), Schodt also talks about how anime and manga’s increased visibility has both helped and harmed the industry, as a vocal minority raises its arms in outrage over content inappropriate for their children (perhaps under the misguided view that because it is animated or drawn, it is automatically for children). The book wraps up with a quick look at how manga is accepted in America today, and a look into manga’s future. This particular section does not ring hopeful for me, as I am firmly against digital media and will not relinquish my precious books until I am dead and cold and buried. The idea that a scarcity of printed works due to a digital uprising leading to an increase in their prices especially turns my blood cold, though I certainly cannot deny its benefits to publishers, sellers, and collectors. That doesn’t mean I have to like it, however.

The presentation of the book is nice. It’s a nicely bound hardcover with a bright cover design. The pages are crisp and clean, as are the art reproductions scattered throughout. Also included is a short color insert depicting excellent covers of several manga magazines. The only negative thing I can really say, is that there is a large collection of rather superfluous charts and graphs inside, that at most are only moderately informative, and at worst are completely silly and a little ugly on the page. I also wish the book’s editor (maybe Schodt himself?) had gone over things one more time, to catch some annoying little errors scattered throughout. Nothing disruptive, just pet peeves of mine. The errors are few and far between, and I can’t fault someone for a few scattered mistakes. However, Schodt’s conservative use of commas does contrast pretty roughly with my love for serial commas, so fellow comma lovers have been warned. This is a good book for both established fans and new fans, though if you’re looking for a more up to date look at the American manga/anime industry, you’ll have to look elsewhere.

By the way, I had forgotten to mention it before, but this past week was the Manga Moveable Feast for Kazuya Minekura’s Wild Adapter, hosted by Manga Bookshelf. You can check out the archive at their site.

Kris

kristin@comicattack.net

@girlg33k_Kris

A copy of this book was provided for review by SBP.

Pingback: Canada case reactions, MMF winds up, DMG assigns first books « MangaBlog